Is my RRSP protected from creditors? Clients are keen to know how bankruptcy affects this key savings vehicle.

Whether it’s nervous clients reviewing their depleted nest eggs, or troubled clients readjusting to a job loss, this is one question financial advisors have probably been asked fairly often in recent times.

The easiest answer is: Indeed—in the case of bankruptcy—except for deposits made within the 12 months leading up to the bankruptcy.

And isn’t it rather fortuitous that the federal bankruptcy amendments, exempting RRSP/RRIF assets from seizure in a bankruptcy, came into force just about a year ago, July 7, 2008, right around the time financial markets began to show us quite forcefully what had been brewing within the economy.

Short of bankruptcy, creditor protection would depend on the type of plan being held, whether it is lifetime or estate protection at issue, and what province or territory the client currently resides in.

Insurance-based plans

For insurance-based plans, protection is available against lifetime creditors if one or a combination of certain family members—spouse, child, grandchild or parent—is named a beneficiary. In the common-law jurisdictions, it’’s determined by the relationship of the beneficiary to the annuitant; whereas in Quebec it is the relationship to the owner. The distinction is irrelevant in the case of RRSP/RRIFs since the annuitant and owner are one and the same.

Insurance-based plans also allow protection against estate creditors if any beneficiary is named, family or otherwise. In either case, insurance-based plans are not automatically protected, but rather obtain protection if the owner has taken the active step of naming appropriate beneficiaries.

Lifetime protection, generally

British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland allow for lifetime creditor protection through their respective judgment enforcements legislation. No beneficiary designation is required; however, in B.C. deposits within 12 months of a claim remain exposed.

The Prince Edward Island law protects only where a family beneficiary—spouse, child, grandchild or parent—is named.

There’s no legislation enabling lifetime protection for residents of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Yukon, Northwest Territories or Nunavut.

Estate creditor protection

In B.C. and PEI, legislation is in place to assure RRSP/RRIF assets bypass estate creditors, so long as any beneficiary is designated (other than the estate of course).

Case law informs the protection in the remaining jurisdictions. In the 2004 Perring case (Amherst Crane Rentals Limited v. Perring), the Ontario Court of Appeal confirmed that non-insurance RRSP/RRIFs flow directly to a named beneficiary, out of the reach of estate creditors. The relevant phrasing in the Ontario law is the same or similar to legislation elsewhere. While not a certainty, this case would therefore likely have strong influence in those other jurisdictions — Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

The 1997 Clark decision (Clark Estate v. Clark) from the Manitoba Court of Appeal held that RRSP proceeds had to be paid back by a named beneficiary to an insolvent estate, until creditor claims were satisfied. While this has not been directly overruled, it has also not been followed on occasion, so that leaves some uncertainty in Manitoba.

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in the Thibault decision in 2004 (Bank of Nova Scotia v. Thibault) that a particular RRSP did not constitute an annuity for Quebec purposes, and therefore was available to estate creditors. While Quebec intended to remedy the legislation, the consensus from the legal community is that it falls short, and therefore it remains that RRSPs likely are exposed to creditors.

TFSA creditor protection

Insurance-based TFSAs are likely to be treated the same way as insurance-based RRSPs.

For non-insurance plans, provincial or territorial laws have been amended (or will be in the near future) to allow beneficiary designations. Once in place (some have had to be re-drafted), protection against estate creditors will likely be the same as with RRSPs. Even so, the local law should be confirmed before relying on financial institution forms.

One thing is certain though, no province or territory has granted lifetime protection to TFSAs.

Certain conditions and classes of creditors may override technical compliance with the rules, even for insurance-based plans.

If a creditor is able to show a fraudulent conveyance or preference, impugned transactions may be reversible. It depends on the province or territory whether intent is a necessary component of the action, or if prejudice to the claimant is sufficient.

It’s possible that matrimonial property, support orders and dependants’ relief claims could impress a trust upon RRSP/RRIF assets. In addition, CRA has been successful in actions taken against registered plans.

Where any of these complications are present, legal advice should be sought out before making any moves.

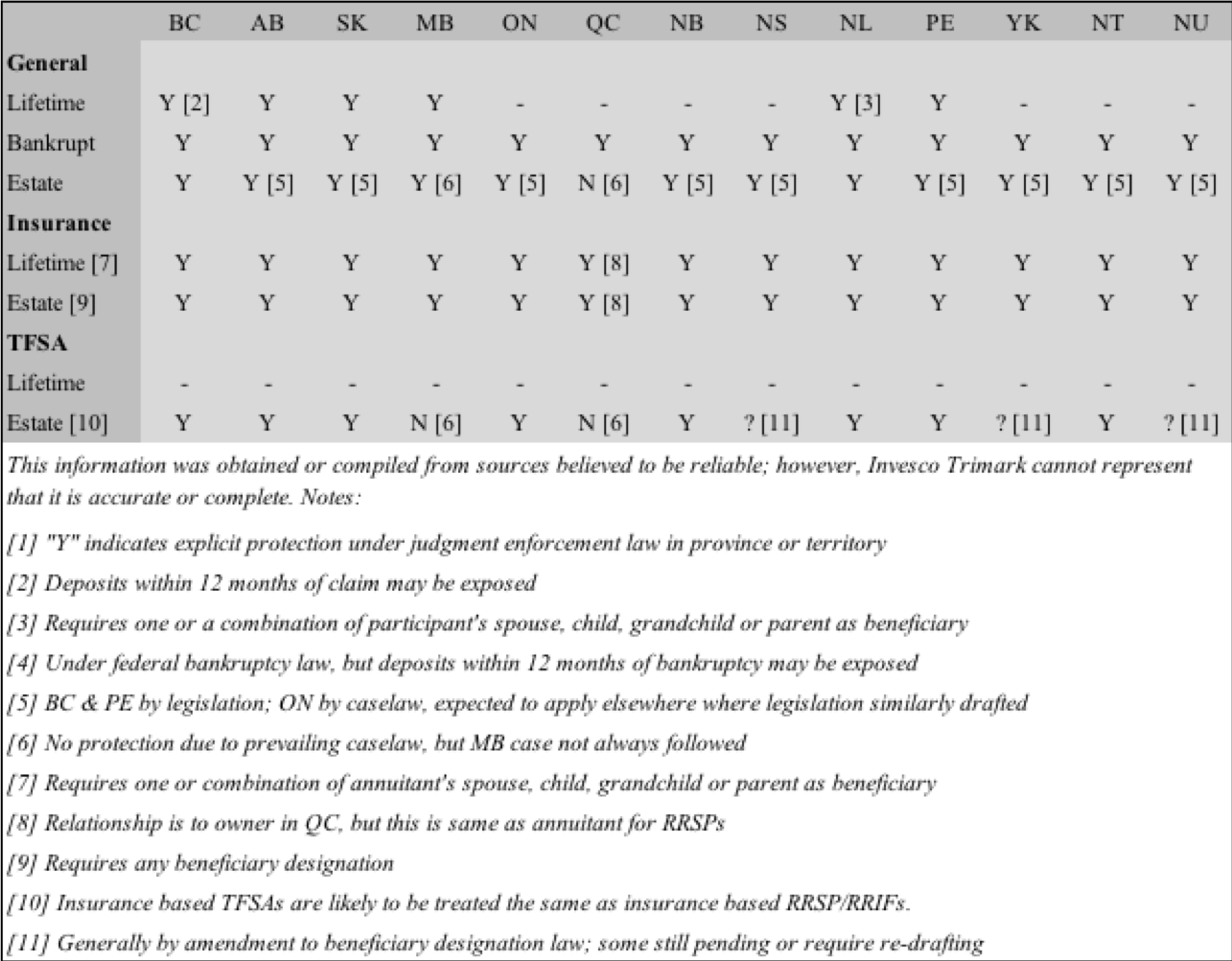

TABLE: Expected creditor exposure

The chart below summarizes expected treatment.