How tax results can hinge on how fees are paid

There is a longstanding debate whether an investor is better off paying through a mutual fund’s management expense ratio (MER), or by direct fee to an advisor in a fee-based account.

The direct fee is favoured by some advisors and investors as it is more transparent than MERs, and can show the total fees on a portfolio in one place. In turn, the investor can clearly see the after-tax cost of such fees when claiming the deduction on his or her annual income tax return.

Still, the question remains whether a direct fee allows for a larger tax deduction, is neutral, or may be more costly in some cases – all issues being addressed in this bulletin.

Criteria for deductibility

As a tax principle, deductibility generally requires that a particular outlay is related to earning taxable income. The further removed from that core purpose, the less likely the outlay is to qualify.

For investment counsel fees, the financial advisor must be advising on the buying or selling of individual shares or securities, or pooled securities like mutual funds. This may include administration or management services related to those securities. Such advice or services must be the advisor’s principal business.

Non-registered accounts

Comparison using fully taxable income

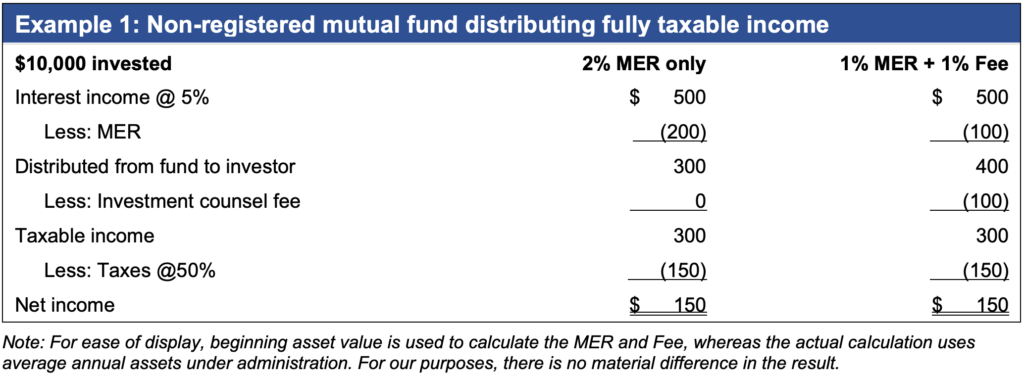

To illustrate the tax effect, we’ll keep the advisor’s advice and compensation the same, whether payment is by MER or direct fee (“Fee”). Either way, the total cost to the investor will be 2% of the assets under management.

Our investor has $10,000 to place in either an A-series mutual fund with a 2% MER, or a 1% F-series version that leaves room for the advisor to charge a direct fee of 1%. To simplify the arithmetic, we’ll assume our investor is at a 50% marginal tax rate, and that the fund’s only income for the year is a 5% interest return.

In both columns, the MER reduces the initial investment return, thereby reducing the amount of income available for distribution to the investor. Once the direct fee is charged by the advisor to the investor at the second step as shown in the right column, the investor is left with the same taxable income and net income under either method.

As illustrated, there is no difference when the amount of fully taxable income – interest and foreign dividends – is at least as much as the MER of the A-series mutual fund.

Preferred income distributions

Of course, not all investment income is fully taxable. Canadian dividends benefit from the gross-up and tax credit procedure. Capital gains are not taxed until realized, with a 1/2 income inclusion for individuals on the first $250,000 of gains in a year, and a 2/3 inclusion thereafter. (The 1/2 rate is used in the examples in this article.) If the fund has preferred income, does this lead to a preference for either MER or direct fee? The answer is “no”.

A mutual fund is subject to very high tax rates, near or beyond 50% depending on the province where it is headquartered. It would be costly for investors as a whole – and particularly for those below top bracket – if the mutual fund was to pay income tax, especially if applied against preferred income. Accordingly, once MERs are applied against income, a mutual fund will always distribute any remaining income to investors.

Under either method/column in Example 1, this will be an additional distribution of the same amount of preferred income to the investor. Whatever the investor’s tax bracket, the net income will be the same either way.

Registered investments

Recall from earlier that deductibility depends on whether an investment is able to produce taxable income. Accordingly, there is no deductibility when an investor pays a direct fee to an advisor for advice on RRSPs, RRIFs or TFSAs, all of which produce tax-exempt income. This is so even though withdrawals from the first two retirement account types will eventually be fully taxable.

RRSP or RRIF holding mutual fund

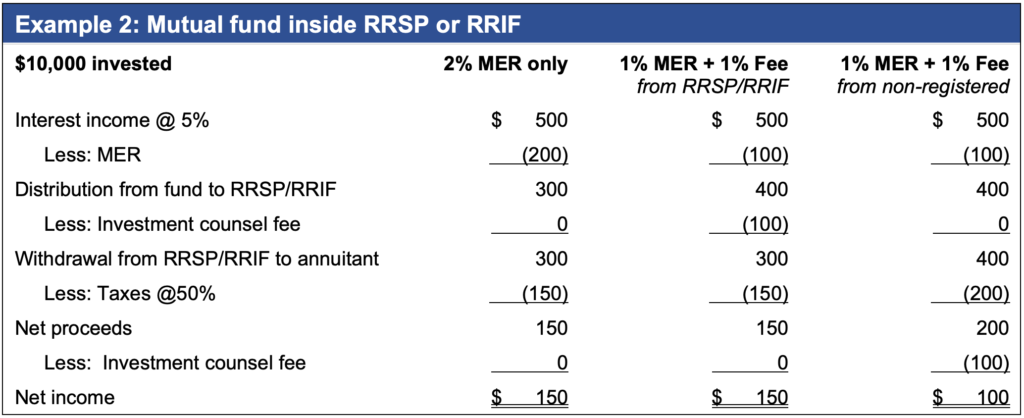

When a MER is charged within a mutual fund in a RRSP/RRIF, it reduces the fund’s investment return, just as it does for a mutual fund in a non-registered account. However, if a fund series with a reduced MER is used to allow a direct fee to be charged, the net tax result to the plan annuitant depends on the source used to pay that fee.

All money within a RRSP/RRIF is yet to be taxed, whether in a mutual fund or in the form of cash. A direct fee may be paid by a RRSP/RRIF trust using pre-tax cash held inside the account, effectively achieving the same result as when a MER is charged within a mutual fund. On the other hand, if the RRSP/RRIF annuitant pays a direct fee using non-registered/after-tax money, no deduction is allowed.

To illustrate the distinction, we’ll add a column in Example 2. The left column charges full MER, while the middle and right columns have a reduced MER plus a direct fee, respectively paid from within the RRSP/RRIF or out of non-registered/after-tax money. To show the final after-tax result, the income will be immediately withdrawn by the RRSP/RRIF annuitant. Though the amount available for withdrawal is highest in the right column, once the non-deductible direct fee is paid, the net income is $100 compared to $150 under either of the other two methods.

It should be noted that in order to show the after-tax comparison on the bottom line of Example 2, the non-registered money is actually sourced out of the RRSP/RRIF.

Instead, what if there were no distributions, and the direct fee in the right column was paid using a (non-registered) $100 bill you already had in your pocket? That would preserve $400 of RRSP/RRIF in the right column, which is $100 better than the $300 in the other two columns. More tax-sheltering room must be better, right?!

As appealing as that first appears, it’s an illusion until the tax is reconciled. If you cash out the $400 in the right column, you’re left with $200 after-tax. For the other two columns, your $300 nets to $150 after-tax, to which you can add the $100 bill in your pocket to total up to $250, still $50 better than paying a non-deductible direct fee.

TFSA holding mutual fund

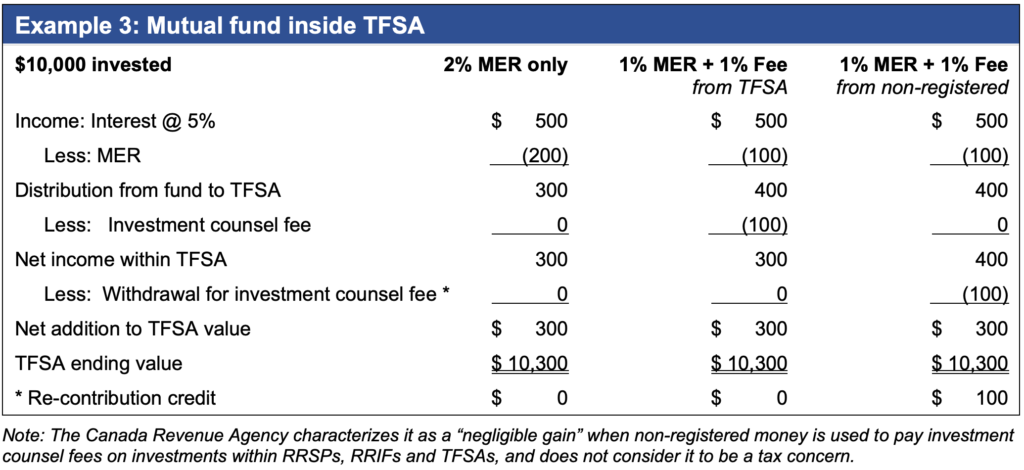

As mentioned above, TFSA income is tax-exempt, so direct fees are not deductible. The net income of a mutual fund inside a TFSA will be the same whether fees are paid by MER, by direct fee from within the TFSA or by direct fee via a non-registered account.

But what about this idea of preserving tax-sheltering room by paying a direct fee from a non-registered source? As we just saw, that didn’t work out with RRSP/RRIFs, owing to the fact that later withdrawals from that type of registered account are taxable. By contrast, when a direct fee is paid from outside a TFSA, the preserved tax-sheltering room will ultimately be delivered through to the planholder as a tax-free TFSA withdrawal.

An alternative way to illustrate this is to assume that the TFSA itself is the cash source for the direct fee, as shown in Example 3. By any of the three column/methods, the net increase for the TFSA is $300. In the first two columns, all the money remains within the TFSA, but in the right column the planholder makes a $100 withdrawal to pay the direct fee, giving the planholder a $100 re-contribution credit the following January 1st.

Related considerations

Financial planning

Financial planning addresses a person’s overall financial needs, including budgeting, saving strategies, credit/debt education, and tax and estate planning. To provide context and foundation for investment recommendations, financial advisors may engage in financial planning discussions and prepare formal plans.

As important as these services are in providing the personal context for investment advice, they are not directly related to earning income, and therefore any fees charged for financial planning are not deductible.

Tax preparation

Personal income tax return preparation fees are generally not deductible, regardless who is preparing the return. But if part of the preparation fee relates to calculating and reporting the details of business income and/or investment income, that portion may be deductible. For those whose income is derived principally through business income and non-registered investments, this could arguably amount to almost the full preparation fee.

It’s helpful if the fee’s components are itemized—or better yet, if the preparer renders a separate invoice for the business and investment-related fees.

Not applicable to segregated funds

Segregated funds are sometimes described as the insurance industry’s version of mutual funds. Despite the similarities to mutual funds, segregated funds are legally structured as annuity contracts (a form of life insurance) whose value fluctuates with a pool of investments that the insurer ‘segregates’ from its other assets.

The current position of the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) is that a segregated fund is not a share or security, and therefore no deduction is allowed for investment advice related to the purchase or sale of segregated funds.

Reasonableness

There is a general requirement under the Income Tax Act that in order to claim a deduction, the outlay or expense must be reasonable in the circumstances. Reasonableness could be an issue if:

-

- A combined fee is levied for financial planning, tax preparation and investment counseling, allowing the client to choose how to allocate that among the services

- A single investment counsel fee is charged, covering RRSP/RRIF, TFSA and non-registered accounts, allowing the investor to determine how much is related to each account type

- Investment fees are pooled for multiple family members and charged disproportionately to one of them

- A higher fee is charged on non-registered assets compared to registered assets, even though the advice and/or service is otherwise indistinguishable

In all these situations, the investor’s deduction claim could be questioned as to reasonableness, bearing in mind that the legal onus lies with the taxpayer to prove entitlement to a tax benefit, not upon the CRA to disprove it.