Tax truth about the PRE

The family home is a place of comfort and stability, and a significant store of wealth. And while there are upkeep costs involved, owners generally expect that they will benefit from rising real estate values.

But could that real estate growth be eroded by tax?

Fortunately, the principal residence exemption (PRE) is one of the most generous tax benefits we have, enhancing the appeal of home ownership by eliminating the tax on capital gains.

Qualification criteria

Type of housing

For the PRE, the property (including land up to one-half hectare) may be a detached or semi-detached house, townhouse, apartment, or part of a duplex or multi-plex; a condominium or share of a strata corporation; a share in a co-operative housing corporation; a vacation property like a cottage, cabin or chalet; a trailer, mobile home, or houseboat; and even a life lease arrangement or similar disposable leasehold interest.

It surprises many people to learn that the PRE applies not only to property in Canada, but also to foreign property that otherwise meets the criteria. Still, one must typically be a Canadian resident to make use of the PRE.

Ordinarily inhabited

To qualify as a principal residence, a property must be “ordinarily inhabited” in the year by the taxpayer, a current or former spouse or common-law partner (CLP), or a minor child. Note that in 1993 the term spouse was extended from married persons to include a common-law spouse of the opposite sex, and the latter term was further broadened in 2001 to include a person of the same sex under the new term common-law partner.

There is no minimum number of days that the property must be occupied in a year to qualify. Further, if more than one property is owned, the claim does not have to be made on the property that is more frequently inhabited.

If the main reason for owning the property is for income and/or capital appreciation, it will not be considered to be ordinarily inhabited. However, incidental rental income is acceptable, again as long as that is not the main purpose of owning. Even if the main reason is nonetheless to earn income, if it is rented to the owner’s child who lives there, then it may still qualify for the PRE. It is a question of fact whether a property is ordinarily inhabited, so legal advice should be obtained to clarify expectations if any of these factors are present.

Who may be the owner?

Whatever type of property it may be, the central condition is that it must be owned (that is, not rented) in order to claim the PRE. Usually the taxpayer must be the owner, though it may also be available in other ways:

Trust

If a person is a beneficiary of a personal trust, the trust may claim the PRE. The ordinarily inhabited requirement applies to that trust beneficiary, his/her current or former spouse/CLP or minor child.

Partnership

A partnership cannot claim the PRE, but a partner may use the PRE to offset a capital gain on qualifying property that is allocated from the partnership. Again, the ordinarily inhabited requirement must be met.

Corporation

While a corporation could own a property in which a shareholder resides, corporations cannot claim the PRE. Also be aware that if a shareholder makes personal use of corporate assets in this way, it will likely be treated as a taxable benefit based on how much it could have been rented to someone at arm’s length.

Calculating, reporting and claiming the exemption

From per-person to family unit

From 1971 when Canada began taxing capital gains, each person could claim the PRE, though it could only apply to one property for any taxation year. This allowed couples to multiply the PRE, for example by having one of them on title to the house and the other on a vacation property. In 1981, the rules changed to limit it to one property per family unit, generally meaning the individual, a spouse/CLP and their minor children.

When to make the PRE designation

A homeowner does not normally make the PRE designation from year to year. Rather, it is generally only reported in a year when there is a disposition. Dispositions include both actual transfers and deemed dispositions, with the latter including adding an owner to title, death of an owner, and a change in use such as converting a property to or from rental or business purpose.

Prior to 2016, a selling homeowner did not have to report anything if the entire gain could be claimed under the PRE. Now, it must be disclosed on the person’s income tax return for the year of disposition, specifically on Schedule 3 Capital Gains (or Losses). In addition, a Form T2091 must be filed, providing information including the address, acquisition date and cost, and the amount of the proceeds of disposition. Failure to file on-time could result in late penalties up to $8,000, or in the extreme a denial of the PRE.

How does the designation work

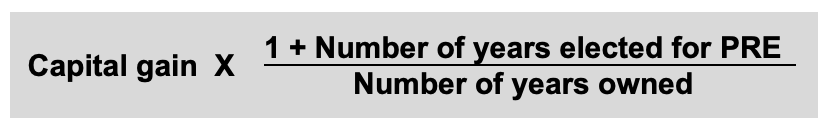

A taxpayer does not select specific calendar years for the PRE, but instead elects what proportion of years to apply it, using this formula:

The purpose of the “1 +” in the numerator is to accommodate for the common situation when there is a sale and purchase of property in the same year. This assures continuity such that the second property does not lose a year of claim, but does not confer any extra benefit as the PRE can only reduce the tax on a calculated gain to zero.

The purpose of the “1 +” in the numerator is to accommodate for the common situation when there is a sale and purchase of property in the same year. This assures continuity such that the second property does not lose a year of claim, but does not confer any extra benefit as the PRE can only reduce the tax on a calculated gain to zero.

Provisos and pitfalls

Here are some more issues to discuss with a lawyer when buying, selling or considering a change in property use:

Legal and beneficial ownership

The PRE is based on beneficial ownership, which may not be the same as who is on title. It is the taxpayer’s onus to prove the nature of ownership if it is questioned. This is relevant in common law provinces, but under Quebec civil law, legal and beneficial ownership can’t be broken apart.

Renting a property

Despite the ordinarily inhabited rule, a property can be rented up to four years and still have those years qualify under the PRE, as long as a required tax election is filed. This may extend beyond four years if the reason for the property being rented is employment relocation of the taxpayer or spouse/CLP.

Former spouses

If the PRE is claimed by one party on a post-relationship disposition, the other party’s PRE entitlement will be limited or eliminated on his/her property if the two properties had been concurrently owned during the relationship. For certainty, a written separation agreement should address ongoing property dealings.

Elections for a deceased person

An executor may use Form T1255 to make the designation for a deceased person. If the deceased owned multiple properties, that designation could affect estate distribution if properties devolve to different beneficiaries. The testator’s Will could provide direction if there are any issues of this sort.