A Seinfeld inspired tax insight on staying the course

None of us will look back on the COVID-19 pandemic with a feeling of nostalgia. Apart from the health dangers, many struggled with self-isolation and social distancing. Still, for many families like ours, we cherished the opportunity to re-connect in ways we hadn’t in years, like dusting off board games, semi-regular family walks, and catching up on some classic TV, like Seinfeld.

In fairness, the show had a bit of a slow start, but it didn’t take long for it to hit the stride that took it to the top over its ten-year run. Now more than three decades since it hit the air, there really is something about the sitcom that came to be known as a show about nothing.

That worked in the world of sitcoms, and may give us something to consider in dealing with investment portfolios.

A conscious nothing

I’m certainly not suggesting that investors set up portfolios once, and ignore them thereafter. On the contrary, it’s imperative to be conscious of economic developments – such as how a global pandemic can derail global financial markets – as well as any developments in the businesses behind individual securities held.

The investor can look to her financial advisor as a source of this kind of information. Together they can review the information to determine what’s relevant (including the effect on the investor’s appetite for risk) and decide if adjustments are warranted. Those may be portfolio changes, behavioural changes, or both – or nothing at all.

The critical point is to resist the urge to make change for the sake of change alone.

Nothing and taxes

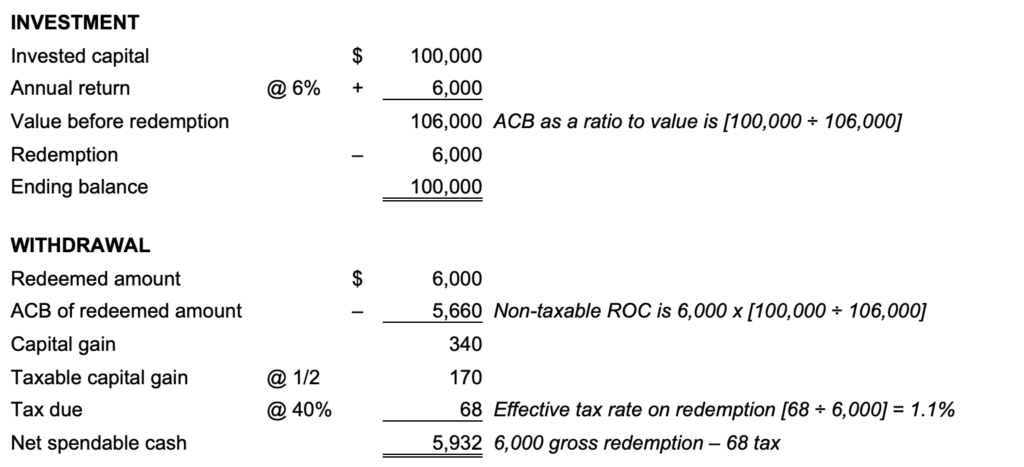

That urge to ‘just do something’ can be particularly harmful to a non-registered portfolio. Unlike registered accounts, changes to non-registered holdings can result in taxable dispositions. Tax deferral that an investor enjoyed while holding rising securities over the course of years will be realized when those securities are sold.

If those portfolio changes are based on an informed and focused review, then the tax implications should not stand in the way of taking that action. However, if the original portfolio continues to suit the investor’s planning needs then a premature change not only drifts away from the plan, but also compounds that diversion by triggering taxes unnecessarily.

This was complicated enough over the last couple decades or so since 2000 when half of capital gains were taxable. Then came the 2024 Federal Budget that increased the inclusion rate to 2/3 of realized capital gains, while preserving the 1/2 rate on the first $250,000 of an individual’s capital gains in a year. For modest portfolios, this change will have little effect on decisions, at least for now. But as compounding continues over many years and decades, this dual-rate structure will become more of a factor in portfolio decisions.

A tale of two investors – Gerry & Jorgé

Consider sister and brother investors, Gerry and Jorgé, 40-year-old fraternal twins saving for a big trip together for their 50th birthday. Both are high income so we’ll assume a 50% marginal tax rate, while using the 1/2 capital gains inclusion rate as neither expects significant capital gains any time soon.

Ten years ago, each used $10,000 to buy 1,000 units of VanDelayed mutual fund for $10 per unit. The price rose as high as $18 but has since come back to $14. It pays no dividends. Despite the recent price decline, Gerry leaves her investment alone.

Jorgé, on the other hand, is convinced that VanDelayed will continue to fall, so he sells. With a fair market value of $14,000 and a $10,000 adjusted cost base, he realizes a $4,000 capital gain. As half the capital gain is taxable, he has a $2,000 taxable capital gain that costs $1,000 in tax, leaving him with $13,000.

A couple months later Jorgé reconsiders and decides that Gerry was right. As it turns out, the price is again $14 when he reinvests his $13,000.

Ten years later when it’s time to book the trip, VanDelayed is at $28.

-

- Gerry’s $28,000 holding realizes a $18,000 capital gain, resulting in $4,500 in tax, netting to $23,500.

- With the price doubling from $14 to $28 from the time Jorgé reinvested, his $13,000 rose to $26,000. Taking away $3,250 tax due to the $13,000 capital gain, Jorgé is left with $22,750.

Despite that Jorgé got back in at the same price as when he exited, the early tax payment hampered his growth, in this example putting him $750 behind Gerry. And though the amount of difference would vary depending on the growth rates at the two time points, as long as there was growth then the difference would never come out to nothing … which is something to think about.