Business succession planning that puts tax on ice

There is perhaps no greater satisfaction for an individual taxpayer than to be able to tell the tax collector, “Just wait!”

This is stated with the full respect that as a society we require a properly functioning tax system to enable our economy to operate effectively. That aside, if there are legal means available to defer a payment then we would be remiss not to explore how to put tax on ice.

An “estate freeze” is a term most often attached to the succession planning activities of a small business entrepreneur. However, the same principles can apply to portfolio investors and owners of real estate in appropriate circumstances , as we’ll touch on at the end of this article.

What is an estate freeze?

An estate freeze is a commonly available wealth technique that can make the succession of selected assets more tax efficient. In this context, the term ‘tax efficiency’ may be a combination of:

-

- The deferral of a taxpayer’s existing inherent tax liability from a current to a future payment date, often aligned with the taxpayer’s death or a spouse’s later death

- The transfer of future growth and tax liability from a taxpayer to a child, grandchild or other person, usually extending time horizons and possibly accessing lower brackets

- The potential ongoing management of the timing and distribution of tax on the growth using currently-existing, newly-created or future-planned trusts, partnerships or corporations

While the legal structure and components may vary, the general principle of a freeze remains constant: Lock in the value of chosen assets without triggering tax (or consciously triggering a controlled amount of tax), while deferring the tax on future growth for years or even decades.

Purpose of a freeze

These tax benefits must follow from the core purpose of an estate freeze, which is to facilitate the orderly transition of selected assets to those whom the taxpayer wishes to benefit, generally being those to whom estate assets would otherwise pass in the traditional sense. (As children are the usual recipients, that will be the term used from here on, but it is certainly possible to pass on to later generations and to non-family recipients if desired.)

The bonus with an estate freeze is that, by managing the tax liability early on, more can be expected to pass on.

Ready to proceed?

The decision to undertake an estate freeze must be considered very carefully. Invariably it involves changes to legal ownership of assets – and it is often irreversible once implemented. It is important for the parent (or freezor) to ensure that there will be adequate assets remaining under his/her ownership and control to continue to live a comfortable life without the burden of tax and legal implications.

The ultimate benefit of the estate freeze accrues to the children carrying on after the parent has passed on. The goal of the freeze is to allow for the greatest value to be received by the children, and the early crystallization of tax in a freeze can assist in that regard. However, care should be taken not to place too much attention on the tax part alone – and the early timing in particular – as that could expose assets to even greater loss risks, possibly cutting off other planning options.

While it may be technically possible to freeze an estate at almost any point in time, it may be ill-advised or at least premature to do so in situations where:

-

- The candidate freezor is young, possibly unattached and without children, bringing into question whom the freeze will favour and whether that is a desired permanent result

- The candidate’s children are young (whether they are minors or young adults), making current asset ownership impractical, and even near future ownership an unpalatable prospect

- The candidate’s marriage is not on the strongest footing, raising the spectre of a division of assets, child support and/or spousal support, which taken together could negate the benefits of a freeze (or be exacerbated by the cost of undoing a freeze)

- Despite being at a reasonable age, the children may have marital, creditor, disability, mental health or addiction issues, any of which would tend to influence against implementing a freeze, or if doing so then would warrant very firm strings attached

- Where the candidate is at an advanced age, the tax deferral from the freeze will be somewhat limited in time, and thus the scope of a freeze may in turn be limited, or alternatively coordinated with some strategic testamentary trust planning in the Will

The motivation to reduce eventual tax liabilities must therefore be tempered with the practicality of age, life stage, maturity and vulnerabilities of both the parent as benefactor and the children as beneficiaries. Assuming that these hurdles have been addressed, what does a freeze actually look like?

The business freeze scenario

Take the classic example of an entrepreneur who has invested a significant amount of time and capital into the growth of a small business corporation. Inherent in that built-up growth can be a substantial tax liability, even with the expectation of using the lifetime capital gains exemption (LCGE) for shares of a small business corporation. As of 2024, that can eliminate the tax on up to $1.25M of capital gains. Assuming a positive outlook for business growth, that attached tax liability will only get larger.

In fact, if left unmanaged, the tax bite could inconveniently come due at the entrepreneur’s death, potentially threatening the viability of the operation as a going concern thereafter. This in turn could lead to a fire sale of the business or its assets in a desperate attempt to find liquidity to service the tax obligation, further compromising family wealth.

To contain that tax liability and protect future value, an estate freeze could be implemented as part of a broader business succession process. The components of the larger plan would include:

-

- A detailed analysis of the business itself, and specifically the technical skills required of current and future management and ownership

- A candid consideration of the soft issues motivating the founder, including an honest introspective of personal/parental motivations and expectations

- Tough love – a frank examination of the children, placing their capabilities, limitations and personalities under a bright light

- A consideration of the reactions of stakeholders within and surrounding the business, including employees, suppliers, customers, bankers – and those children who are projected to take on less-favoured roles (whether actual or perceived)

- A review of asset holdings to isolate and realign appropriate assets for tax restructuring, while preserving the integrity of the business

- The freeze date, when pending liabilities are crystallized through creation of legal structures (trusts, corporations or partnerships), execution of asset transfers and necessary tax elections

- An allocation of future growth to the successors through one or a combination of corporate share issuance, beneficial trust entitlement and partnership interest, all in such proportions and subject to such limitations built into those legal structures

- Assuring funding of later estate liquidity by obtaining life insurance coverage aligned to the determined tax liability, usually through joint-last-to-die life insurance coverage for founder and spouse, given the availability of asset rollovers at tax-cost basis between spouses at first death

- Insulating against the children’s risk events through a variety of measures including shareholder agreements, key person insurance for those with active business roles, matrimonial contracts and Will & estate planning

As this series of activities shows, the technical freeze is not so much an end-product as it is a focus feature of a lengthy and potentially very challenging process. Its ultimate form will be dictated by circumstances, being as simple or complex as needs may dictate.

Freeze mechanics

For a business to be of sufficient value to warrant an estate freeze discussion, the existing business form is almost always one or more corporations. (Partnerships may be required or desired in some professions or commercial fields, which will require adjustments to the particulars, but the principles remain the same.) The mechanical procedure is to make adjustments to the entrepreneur/freezor’s share interest so that the current value of the business is frozen, and the future value of the business can be shifted to the children.

Bear in mind that three characteristics must exist across all shares in a corporation. There may be one class of shares that holds all three of these characteristics, or they may be divided according to the needs of the circumstances:

-

- Voting control

- Right to dividends

- Right to capital distribution/return, generally on dissolution of the corporation

The most common procedure is for the freezor to exchange current common shares (eg., having all three of the foregoing characteristics) for one or more new classes of preferred shares having a fixed value equal to the value of the original common shares at the time of the exchange. Growth in the future value of the business will accrue to one or more other share classes. The preferred shares will have features that preserve both value and control (with these two elements sometimes distributed among share classes), generally including:

-

- A corporate redemption option and shareholder retraction option, both aligned with the current/freeze value of the corporation

- A priority right to return of capital if there is a wind-up of the corporation – This priority is against all other share classes, but does not guarantee the full return of capital if corporate assets have been depleted or there are superior creditor claims

- Voting control (or at least participation), to allow the freezor to monitor activities and possibly re-assert management control over the business

- A dividend – the preference, accumulation and triggering features of the dividend can be catered to the freezor’s needs and desires

- Of key importance, a ‘price adjustment clause’ to provide protection (though not a guarantee) against future tax liability should the freeze share valuation be challenged by Canada Revenue Agency

The freeze shares will often remain outstanding until the death of the freezor, or last death of freezor and spouse. Alternatively, there may be a redemption schedule as part of a ‘wasting freeze’, whereby the freezor is eased out of the business, both from a financial and a control perspective. This latter approach may be part of long-term tax strategy if the freezor is at less than top marginal tax bracket in very senior years, so that some of the tax liability can be triggered in a controlled manner, rather than awaiting an inevitable large tax bill in the estate.

A progression of freeze examples

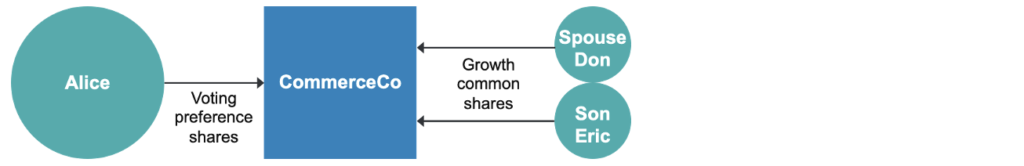

Let’s consider entrepreneur Alice Bolton and her successful distribution and retailing operation run under her corporation, CommerceCo. Alice has gone through the analysis and is ready to implement an estate freeze. She has a husband Don and adult child Eric.

Simple freeze

Alice and her professional advisors may be content that there are no serious complications to the business or the people involved. Accordingly, they’re content to have an arrangement with the least moving parts. Alice could do a basic share-for-share exchange to complete the freeze and have the growth shares issued directly to Don and Eric. Whether Don would be included in this manner would depend on valuations and respective wealth positions of Alice and Don.

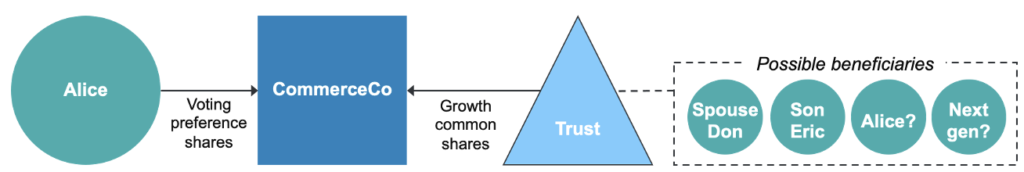

Freeze with added family trust

On further consideration, following conversations with her legal advisors, Alice might be a little concerned about the untethered wealth transfer to son, Eric. She may be especially uncomfortable with the potential that his interest in the business could be exposed to his creditors, open to matrimonial claim with a later spouse and generally be subject to his own lack of maturity. By adding a family trust as a layer that separates beneficial entitlement from legal ownership, Alice can take some solace that these risks are mitigated, particularly if she is a trustee of the trust.

Freeze with additional corporations

With input of her tax advisors, Alice may conclude that one or more additional corporations may be desirable:

-

- A holding corporation (HoldCo) interposed so that excess cash may be paid by tax-deferred dividend from operating company (OpCo) to Holdco – This can protect against Opco creditor claims, while preserving Opco’s tax status for Alice (and possibly Don and Eric) to be able the claim the LCGE

- A breakout of OpCo into a RetailCo and DistributeCo, based on distinctive business needs and to prepare for a potential later spin-off

- A RealtyCo may be established to isolate real estate (particularly when those assets are no longer need for business operations), based again on preserving LCGE status, as well as non-business liability exposure

As can be appreciated, the legal and tax issues become increasingly complex as dollar values, number of holdings and parties to the proceedings increase. The estate freeze can usually be scaled upward to capture such concerns. However, implementation costs will also rise, which may become difficult to justify when planning against more remote contingencies.

The investment or real estate freeze candidate

As mentioned at the outset, the principles of an estate freeze need not be limited to business situations.

-

- A very simple version of this would be for a portfolio investor or owner of real estate to make an outright transfer to someone else. While any as-yet unrealized capital gains would be triggered (except any spousal rollovers), this may be an acceptable trade-off if the primary goal is to push future growth into the hands of others.

- With greater complexity of assets and/or parties, corporations or trusts could be used to implement a freeze involving passive investments or real estate.

- For wealth generated within an active business corporation and migrated into a holding company, the strategies used in the business estate freeze may be transported with some limited modification into an investment or real estate freeze.

Both the formal rules and their interpretation by the Canada Revenue Agency can (and do) change from time to time, so in all cases the assistance of tax professionals is a must before taking any action.

Variations for later planning

Thaws, melts, gels and re-freezes are cute terms used to describe sophisticated planning alternatives for contingencies that may arise down the road.

The key issue to recognize is that, with the right planning, there is great latitude in how an estate freeze may be structured from the beginning, including the flexibility to build upon, re-cast or undo the process, as later circumstances may require.