Exposure when owning American property at death

As Canadians, we may expect (though not look forward to) tax being imposed on us by our government at death. In particular, the value of tax-sheltered retirement accounts is brought into income at death, as are the capital gains on the deemed disposition of capital assets – both of which may be deferred by transfer/rollover to a spouse or common law partner (CLP).

For those owning property in the United States at death – ranging from real estate to financial assets to personal belongings – there may be US Estate Tax due (capitalized in this article to distinguish from generic tax references), and US estate filing obligations even if no such tax is owed. The tax is based on gross value, not just the capital gain that Canada targets, and even when there is a rollover to a Canadian spouse/CLP. As well, US financial assets are counted whether in non-registered form or in tax-sheltered accounts like RRSP/RRIFs and TFSAs.

Whether you are pre-planning against your own future exposure, or acting post-mortem as an executor, professional advice is imperative in this extremely complex area. This article outlines the key terms and major steps involved, to help prepare for that professional engagement.

Who is exposed to the Estate Tax?

This article focuses on the tax and estate implications for Canadians who own US property at death, with emphasis on the Estate Tax. To lay the groundwork, we begin with an overview of how that regime applies to Americans domestically, paving the way for the discussion of its application to Canadians that follows.

US citizens and domicilliaries

The Estate Tax applies to the worldwide estate at death of US citizens wherever they may be living, and of

non-citizens domiciled in the US. Domicile is like residence, though technically based on a person’s country ties.

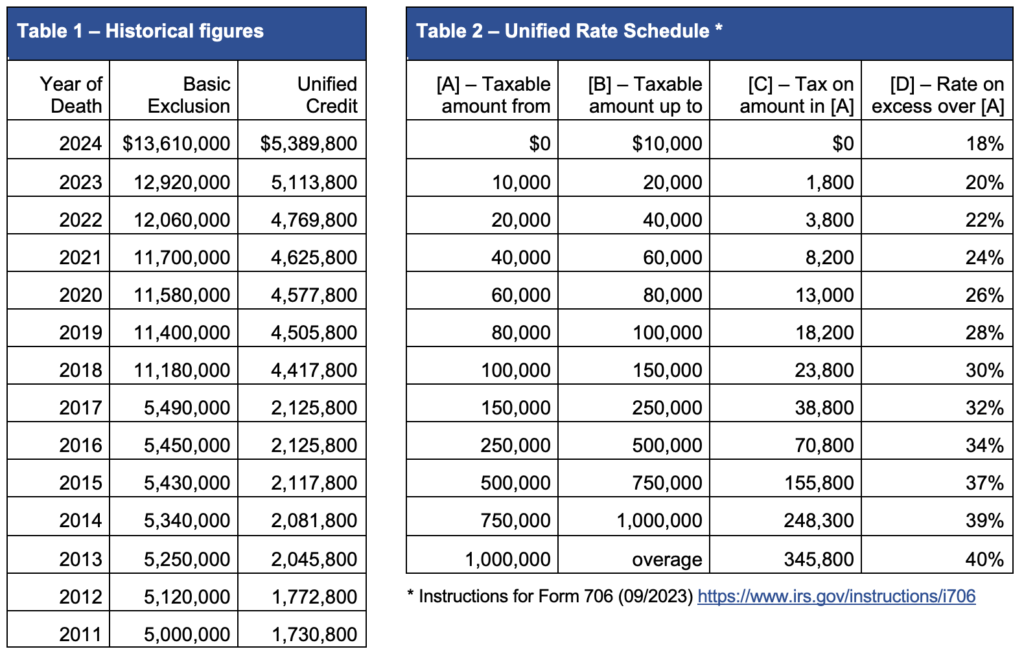

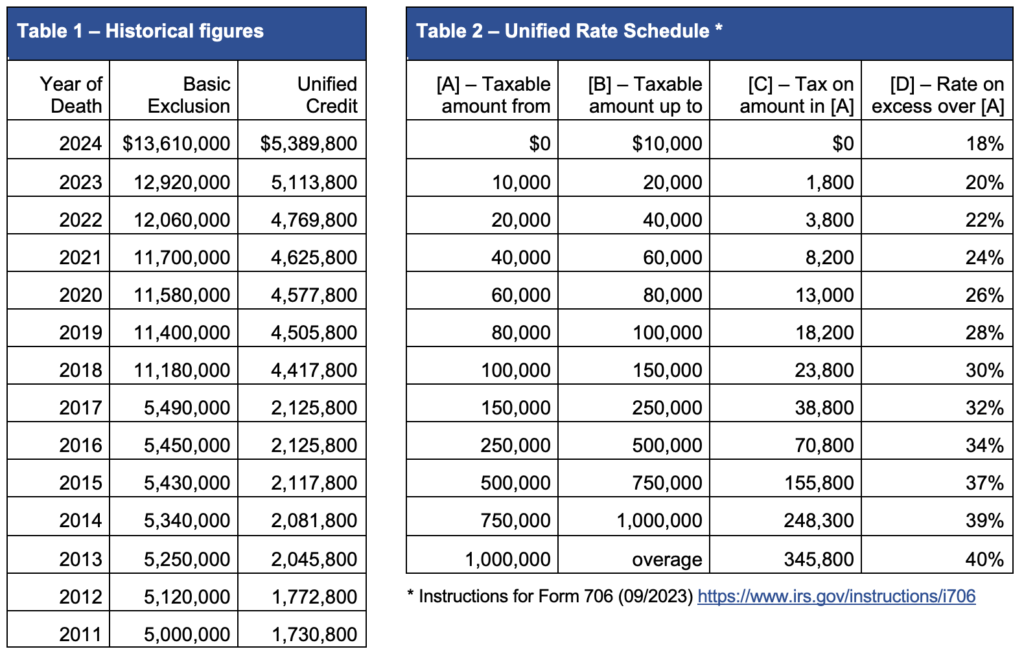

If the fair market value (FMV) of a deceased’s worldwide estate exceeds the year’s asset exclusion amount – US$13.16 million in 2024 – tax may be due on the amount over that threshold. Historical exclusion amounts are shown in Table 1 on the last page of this article. Though the table shows increasing amounts year-to-year, it is slated to return to its pre-2018 indexation formula in 2026 (roughly halved to about US$7 million), absent further legislative changes.

Credits and deductions are then applied to reduce this preliminary figure to the amount upon which the tax is calculated, applying graduated rates ranging from 18% to 40% as shown in Table 2 on the last page of this article.

In addition, the US has a gift tax and generation-skipping transfer tax (GSTT). The gift tax applies to lifetime transfers above an annual exclusion amount per donee, currently US$18,000 in 2024. The GSTT limits transfers to beneficiaries at least two generations younger than the donor/giver. Without getting into the arithmetic, to the extent that the gift tax and/or GSTT apply during lifetime, this can erode the asset exclusion amount for the Estate Tax.

One important note before continuing: Though the rules and figures are expressed on an individual basis, there are plenty of ways to defer, deduct and double-up when planning with a spouse. Professional advice is recommended.

US non-residents, including Canadians

Relevant to this article, the Estate Tax can also apply to a deceased Canadian who is a non-resident of the US, if:

-

- FMV of the deceased’s US-situs assets (detailed following) exceeds US$60,000, and

- FMV of the deceased’s worldwide estate exceeds the current year’s exclusion, again US$13.16 million in 2024.

However, whereas US citizens and domiciliaries pay based on the full FMV above the exclusion, the calculation for a non-resident Canadian is a proration of US-situs assets to the worldwide estate (again, above the exclusion).

Threshold and deadlines for filing a US estate return, and paying Estate Tax

The executor of a deceased Canadian must be careful not to confuse the test for the Estate Tax with the test for the requirement to file a US estate return. If a deceased Canadian owned US-situs assets in excess of US$60,000 at death, an estate return must be filed with the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS), regardless of the size of the estate. Generally, the executor must include a certified copy of the Will or court order when filing.

The IRS clearance certificate facilitates the executor’s ability to deal with estate assets. Without that proof, financial institutions may refuse to take instructions from the executor, and US real estate transfer agents may be unwilling to register an intended transaction. As well, the estate’s reporting provides the tax cost basis for heirs’ future real estate dealings, without which they may face higher tax on a later sale, or may not be able to sell the property at all.

Important deadlines for executors:

-

- A US estate return is due within nine months of death, along with payment of the Estate Tax. A six-month filing extension is generally granted if application is made before the due date.

- Extension of the Estate Tax payment due date is distinct from an estate return extension. Executors must be aware that while this will avoid late payment penalties, interest will accrue from the original due date.

Categorizing assets

US-situs assets

The IRS defines “situs” as “The place to which, for purposes of legal jurisdiction or taxation, a property belongs.” Though a non-exhaustive list, here are some examples of the most common US-situs assets, also phrased as “US-situated assets” in some IRS publications:

-

- Real estate (including time-shares), generally being the full value even if held jointly with right of survivorship

- Tangible personal property (furnishings, vehicles, boats, art, collectibles) owned and located in the US

- Shares of US corporations (public or private), even in a Canadian brokerage account or registered account

- Bonds and debt issued/owing from a US individual, corporation or government

- US retirement plans, common types being 401K and 403B plans, and individual retirement accounts (IRAs)

- Contents of a safety deposit box in the US, including cash, regardless of currency/country of denomination

- US property held in a trust if the deceased had power of appointment, including an alter ego or joint partner trust

NOT US-situs assets

Some financial assets may have US elements, but due to their underlying structure or the way that ownership is held, they are not considered to be US-situs assets. Some examples, again non-exhaustive:

-

- US securities in a Canadian mutual fund trust or corporation, segregated fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF)

- Personal property that is merely in-transit, for example jewellery worn by a Canadian who dies while travelling

- US marketable securities or investment real estate held in a Canadian corporation, noting however that vacation property may come under IRS scrutiny for avoidance, especially if it is the corporation’s only asset

- American depository receipts (ADRs), as they do not hold US securities

- Deposits in a US bank account (but not US brokerage account), as long as it’s not part of a US business activity

- Excepted US government and corporate bonds under the “portfolio interest exemption”

- US-denominated bonds of a Canadian issuer providing US exposure without holding US securities

- Life insurance on a Canadian who is a US non-citizen/non-resident

Worldwide estate

A deceased’s worldwide estate is determined according to US rules, whether the property is in the US, Canada or elsewhere. This may include assets of significant value, about which careful decisions and actions may have been taken to alleviate or circumvent Canadian income tax or provincial succession issues, but which nonetheless remain countable for the Estate Tax, including:

-

- Canadian registered plans, including RESPs, RDSPs, TFSAs, RRSPs, RRIFs, and survivor pension benefits

- Life insurance owned by the deceased (or sometimes a deceased’s corporation), even with a named beneficiary

- FMV of private corporation shares, after payment of a death benefit from corporate-owned life insurance

- Gross value of real estate and non-registered accounts, even when held jointly with right of survivorship

(with limited exception if the survivor is a spouse with a proven contribution to the asset acquisition)

- Property in a trust considered to be a US grantor trust, likely capturing a Canadian alter ego or joint partner trust

Tax calculation

Once it is determined that a deceased Canadian meets the threshold of both US-situs assets and worldwide estate, attention may turn to calculating the tax liability. The calculation begins with the gross value of the US-situs assets.

Deductions

A variety of deductions and credits may be taken, most of which must be prorated based on the proportion of US-situs assets to worldwide assets. The main deductions are:

-

- Funeral and estate administration expenses

- Liabilities of the deceased at or as a result of death, including foreign (i.e., Canadian) income tax

- Death taxes paid to a US state

- Charitable donations (generally must be made to a US entity, with payment made in the US)

- Non-recourse debt on US property (i.e., lender’s claim is limited to the pledged asset) – Fully deductible.

Taxable estate

The deductions are applied against the gross US-situs assets to arrive at the taxable estate. This figure is then used to calculate the preliminary Estate Tax amount by applying the graduated rates in Table 2.

Unified credit

Any deceased who is a non-resident and non-citizen of the US may apply the unified credit against the calculated preliminary Estate Tax. The minimum unified credit is US$13,000, which is equivalent to the Estate Tax on an estate of exactly US$60,000, as can be verified by viewing columns [A] and [C] on Table 2.

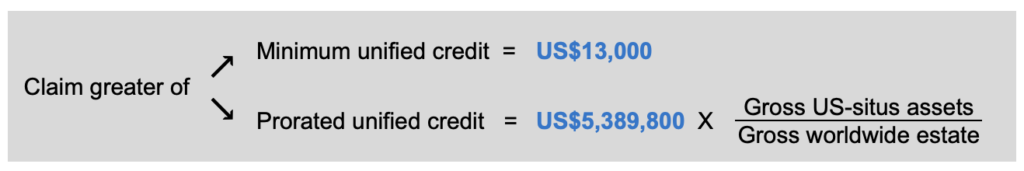

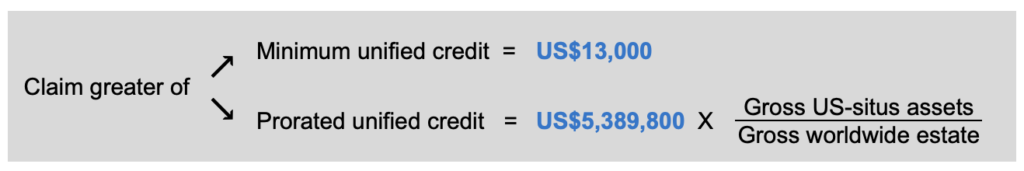

Alternatively, the executor may claim the unified credit under the Canada-US Tax Convention (the “Treaty”), which allows Canadian residents to claim the same as is available to a US citizen or domiciliary – US$5,389,800 in 2024, equal to the tax on a US$13.16 million estate – as can be verified by viewing the first row on Table 1. This is then prorated based on the proportion of US-situs assets to worldwide assets.

Thus, the formula for a Canadian resident is:

Marital credit

The Treaty allows a marital credit for property passing to a Canadian or US resident spouse who is a non-US citizen. It is restricted to legally married spouses as defined under US law. The credit is equal to the lesser of the prorated unified credit and the Estate Tax payable on US-situs assets transferred to the spouse. The net result is that it can effectively double the prorated unified credit.

Canadian federal tax credit for US Estate Tax paid

As noted in the introductory paragraph of this article, Canadian tax law deems capital property to be disposed upon death. This applies to the worldwide assets of a Canadian resident, including US-situs property. As of June 25, 2024, a 1/2 capital gains inclusion rate applies to the first CA$250,000 of capital gains in a year, with 2/3 inclusion applying to capital gains above that threshold. The included amount, or “taxable capital gain” is added to the taxpayer’s income for the year. When a person dies, the terminal taxation year is January 1st to the date of death.

Under the Treaty, a foreign tax credit may be claimed against Canadian federal tax related to US-situs property.

The credit is limited to the Canadian tax liability on that property, noting that there is no terminal year tax on RRSP/RRIF accounts (including any US-situs investments therein) rolled to a surviving spouse.

At present, no province or territory allows a foreign tax credit for the Estate Tax.

Planning options to limit Estate Tax

There are both simple steps and complex strategies that can be taken to reduce Estate Tax exposure. Each has its costs, benefits and drawbacks, with some able to be used in combination, and some mutually exclusive of others. Following here are some approaches that can be explored more deeply with a qualified cross-border professional.

Lifetime gifting or selling

If a given property is not owned at death, then the Estate Tax will not apply, at least not directly. Depending on when and to whom assets are transferred, gifting could affect the eventual exclusion amount available at death. The other immediate consequence to consider is early realization of capital gains that would otherwise be deferred until death.

Relocating property out of the US

Vehicles, jewellery, artwork, collectibles and other personal belongings are considered US-situs property if housed in the US. It may be preferable to transport any such property back to Canada if not required for current living needs.

Choosing/changing form of investments

While US securities are US-situs property, there are ways to have US market exposure that still shields against Estate Tax. One of the simplest ways is to own US mandates in Canadian mutual funds, segregated funds or ETFs. Large accounts can command fees comparable to individual security portfolios, so cost is not a material issue.

Life insurance, with or without an ILIT

Assuming an adequately healthy person, life insurance can provide liquidity to pay the Estate Tax. Unfortunately, the death benefit will be included in the worldwide estate if owned by that person. Alternative owners could be another person or an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT). In the latter case, it is best to have the ILIT acquire the policy from the outset, as there is a lookback attribution to that person if transferred within three years of death.

Non-recourse mortgage financing

Non-recourse debt is fully deductible against US-situs assets without proration based on one’s worldwide estate.

As enforcement is limited to the property being mortgaged, it may be difficult to source a willing lender. Additionally, such arrangements inevitably have higher interest charges and other potentially onerous covenants.

Canadian holding corporation

Assets held in a Canadian corporation will not be subject to the Estate Tax. While beneficial on its own, this must be balanced with the Canadian corporate tax treatment, particularly in light of the increased 2/3 capital gains inclusion rate for corporations as of June 25, 2024. As well, if residential/vacation property is held in a corporation, its use by a shareholder or other non-arm’s length individuals will likely be treated as a taxable shareholder benefit.

Canadian discretionary trust

A trust may be preferable to a corporation for either or both investment holdings and vacation property. Though trusts are taxed at the highest bracket rate (including that they too now face the 2/3 inclusion rate on capital gains), they can often be drafted such that income is allocated to one or more beneficiaries. For vacation property, the terms can allow for its use by a wide range of beneficiaries, and there is no corresponding concern like shareholder benefits with corporations. As trusts are subject to deemed disposition of capital assets every 21 years, periodic monitoring and occasional adjustment or distributions may be necessary.

Distinguishing US and non-US gift recipients

Whether giving in life or at death, it may make things more manageable for the next generation if you isolate or skew the allocation of US-situs property to US persons only. They will have to grapple with US succession rules on all their assets anyway, whereas non-residents will only be exposed if they hold US-situs assets.

US dynasty trust

If you expect one or more of your beneficiaries to remain permanently in the US, an irrevocable dynasty trust may be worth considering. If drafted in accordance with US law, it can minimize the impact of the Estate Tax, gift tax and GSTT, and as a US resident trust it is not subject to the 21-year deemed disposition of capital property.

Reference tables