A primer on the TOSI “tax on split income”

There are many tax benefits to running a business through a corporation.

Operationally, corporate tax rates are generally lower than your personal marginal tax rate. Though personal tax will eventually apply when dividends are paid out of the corporation, in the meanwhile you are able to reinvest more dollars into that business within the corporation.

At the ownership level, you can control the amount and timing of dividends to yourself as shareholder. This allows you to defer the personal income and associated tax until you need cash for personal spending purposes.

If you bring in other shareholders and possibly more share classes, you can also control who receives those dividends. And when those additional shareholders are lower income family members, you may be able to ratchet down the household tax bill. Years ago, it was almost that simple, but today there are increasingly complex rules that must be navigated.

TOSI emerges in 2000 as the ‘kiddie tax’ for minors

A couple of decades ago, it was routine tax planning to pay dividends to family, including minor children. Whether a child owned shares directly or was a beneficiary of a trust that held shares, dividends could be taxed to that child. With little to no other income, the tax would be correspondingly low, and practically the net-of-tax money ended up under the same roof.

In 2000, the TOSI was brought into law to prevent this kind of dividend sprinkling. It applied (and still does) to dividends paid to a child under the age of 18 throughout the year. Despite such dividends being legally paid to the recipient, TOSI causes them to be taxed at the highest bracket rate, essentially ignoring the recipient’s own tax rate.

This is an important distinction from being an attribution rule, where tax is imposed on a person who would have otherwise been entitled to certain income, being the parent in this example when dividends are paid to a minor child. With an attribution rule, it would be a no-better-off scenario if a higher bracket parent was taxed on the dividend. But things are especially unpalatable under the TOSI where tax is automatically imposed at the highest rate, making it a worse-off deal if the parent’s income level is anywhere less than top bracket.

TOSI comes of age in 2018, extending to adults in the family

In 2017, the federal government proposed a variety of changes for private corporations and their shareholders. While some of the proposals were shelved, the TOSI changes proceeded into law in 2018, with TOSI now extending to adults, capturing both adult children and spouses. Fortunately, these new rules for adults are not as unbending as the kiddie tax version. Where there is sufficient economic substance to the involvement of the adult child or spouse, TOSI may not apply.

Make no mistake though, these rules are very (very!) complex. There are new definitions, layers of application, and multiple exceptions. Some of those exceptions have objective criteria, while others require an exercise of discretion on the particular facts. To help, the government has collaborated with external stakeholders to publish examples to guide the application of TOSI in its Guidance on the application of the split income rules for adults, found at https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/programs/about-canada-revenue-agency-cra/federal-government-budgets/income-sprinkling/guidance-split-income-rules-adults.html.

What follows is a high-level outline of the TOSI and its exceptions, using some of the technical terms, but with streamlined phrasing in order to convey the core points. Readers should consult a qualified professional to determine applicability in individual circumstances.

Continuing planning that is not affected by TOSI

It is worth noting that the TOSI rules do not prohibit family members from owning private corporation shares. Though the original 2017 proposals cast the net widely to encompass the lifetime capital gains exemption (LCGE), that part was dropped. Accordingly, it is still possible to plan for sharing future capital gains with family, including the LCGE – of course with qualified professional advice.

Also, TOSI has no effect on the bona fides employment of family members. As long as the wages paid are reasonable in relation to the services rendered, this is simply treated as taxable employment income of the recipient. This is true even for minor children.

Who and what is potentially open to the TOSI rules?

TOSI may apply if a person receives “split income” and is either an adult resident of Canada, or a minor (under the age of 18) who has at least one parent who is a resident of Canada.

“Split income” includes taxable dividends, shareholder benefits and interest payments, from or related to a private corporation. It may also include distributed capital gains where underlying income would have been split income, but generally not capital gains arising on the sale of farms, fisheries or small business shares. Income from a partnership or trust that arose out of rental property may also be caught.

It does not apply to securities or debt of public corporations, government debts, or to mutual funds that hold those listed sources. Deposits with banks and credit unions are also clear of TOSI.

Exclusions from TOSI

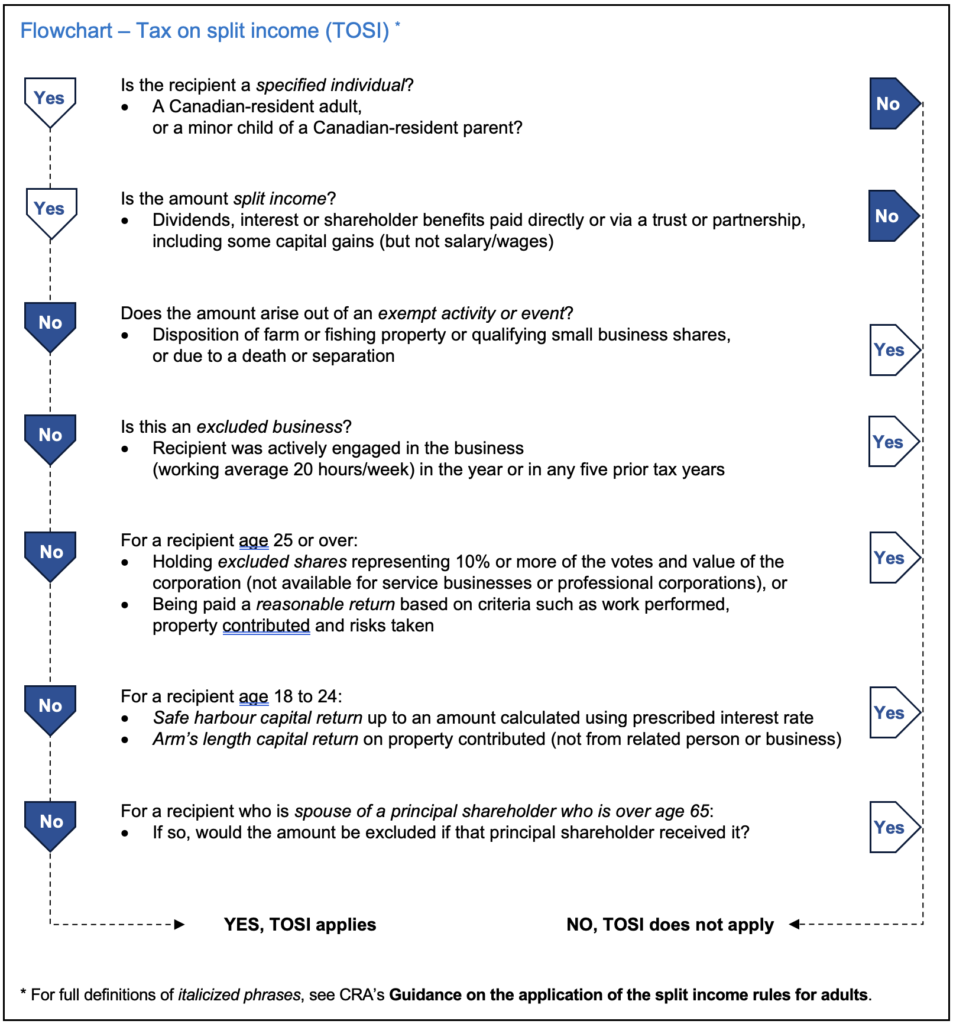

The rules are targeted at circumstances where unintended advantage may be gained. As there remain plenty of reasons and arrangements where family members may hold shares and legitimately be entitled to dividends, the rules allow for several exclusions. For simplicity, we’ll refer to dividends within the following explanations, understanding that split income is in fact broader, as noted above. See the Flowchart on the next page for a graphic representation of the key decisions.

All adult recipients

The recipient has been “actively engaged” in the business in the current year, or in any five years leading up to the year the dividend is paid. The five years do not have to be consecutive. This will generally be met if the person works an average of 20 hours per week. If the business is only active part of the year (eg., seasonal), the working time would be applied to the portion of the year when the business operates. A lesser time commitment may suffice, but that would depend on the facts and circumstances of the case.

Adult recipients age 25 or over

Even if the actively engaged threshold is not met, a dividend may be considered a “reasonable return” based on a combination of factors, including labour contribution, property contribution, risks assumed and historical payments. Importantly, this exclusion is not available where the business is principally a service business or a professional corporation.

Adult recipients age 18 to 24

Younger adults may also be able to claim a reasonable return, but based only on property contributed by that individual, and with the size of the return subject to a ceiling prescribed by formula.

Principal shareholder is over 65, recipient is spouse

Many business owners will have planned their retirement on the expectation of being able to share with a spouse in those later years. Accordingly, if the principal shareholder is 65 or over, dividends paid to a spouse will not be subject to TOSI. This is specifically intended to align with the age for pension income splitting.