Tax treatment of non-registered account decumulation

During accumulation, investors enjoy a tax deferral when the price of their holdings increases. In tax terms, this is known as an unrealized capital gain, and works whether securities are held directly or within a mutual fund. In this article, we’ll use mutual fund examples and terminology.

Later, if the money is not needed all at once, it will usually be taken as a series of annual draws, known as a systematic withdrawal plan (SWP). This spreads the tax by allowing continuing deferral on the remaining investment.

Tax deferral with unrealized capital gains

In registered accounts such as Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs) and Registered Retirement Income Funds (RRIFs), investors are entitled to tax-sheltered growth regardless of the type of income that is earned. There is also no tax as the investment value varies, but when withdrawals are taken, each dollar is fully taxable.

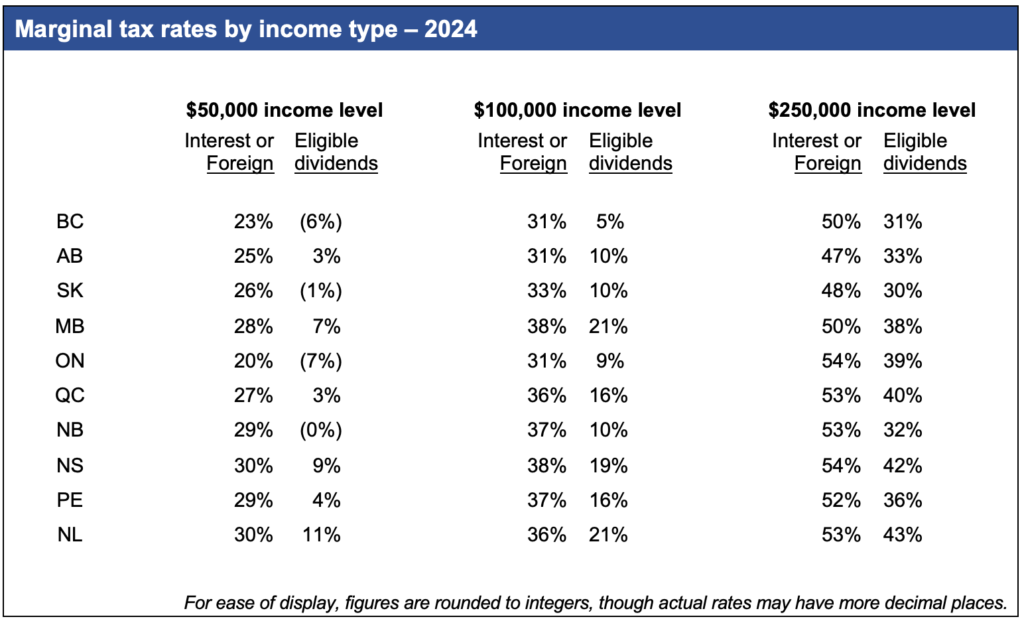

For non-registered accounts, interest and dividends are taxable in the year earned, as are capital gains that a mutual fund realizes and distributes to investors. Changes in the price of underlying securities will cause a mutual fund’s value to change, but no tax arises out of such fluctuations. But when there is a redemption/sale of the fund by the investor, that is a taxable event. And if the fund’s value has increased in the interim then the investor will realize a capital gain at that time. That capital gain is equal to the fund’s fair market value (FMV) minus the investor’s adjusted cost (ACB), the latter being discussed in greater detail under the next heading.

Fortunately, only a portion of the capital gain is taxable. The “taxable capital gain” is derived by applying what is known as the income inclusion rate. That rate has ranged between 1/2 and 3/4 since 1971, but has remained stable at 1/2 since 2000. Now, in accordance with the 2024 Budget, the rate has again risen to 2/3, but the 1/2 rate remains available for individuals on the first $250,000 of capital gains in any year. (For trusts and corporations, the 2/3 rate applies to all capital gains.) The 1/2 rate is used in the examples to follow, on the assumption that the investor is an individual with less than $250,000 of annual capital gains.

Adjusted cost base

An investor’s ACB begins with the amount invested, averaged across multiple purchases. For example, if one mutual fund unit was purchased last year for $4, and one unit this year for $6, the total ACB is $10, which works out to $5 average per unit. The total value as of the second purchase is $12, including an unrealized capital gain of $2.

The “adjusted” part of ACB includes such things as acquisition costs on each transaction, and income that is not distributed but instead reinvested. Notably, the investor is still taxed on reinvested income as if it had been distributed, with the ACB increase ensuring that the investor is not taxed a second time on a later disposition.

Redemption, portion, proportion

As a capital gain is an addition to invested capital, you could think of it as a chocolate-dipped soft ice cream cone. When it comes time to consume it, you could be taxed as if you licked off all the chocolate first (that’s the added portion), or each bite could be treated as some ice cream and some chocolate.

Eating preferences aside, it is the latter biting version that more closely resembles a mutual fund redemption. Each redemption has two portions: ice cream in the form of a non-taxable return of capital (ROC), and chocolate dip that is treated as a realized capital gain. The proportion of each on a given redemption is based on the size of the redemption in relation to the ACB and the current market value. This is best illustrated by looking at a few scenarios.

SWP scenarios

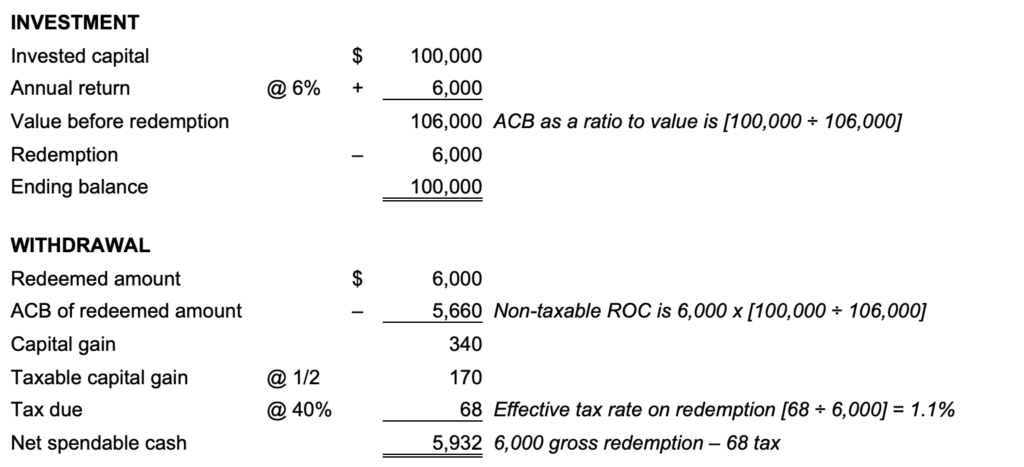

Suppose you inherit $100,000 from a great aunt and decide to use it to supplement your monthly income by $500, or $6,000 annually. You choose a mutual fund you expect to earn a consistent 6% annual return, all in unrealized capital gains. To keep the focus on the SWP effect, we’ll simplify the arithmetic by having you take your withdrawal at year-end rather than monthly. Your marginal tax rate is 40%.

Scenario 1 – Equal withdrawals, maintaining principal

In this first scenario you intend on preserving that $100,000 for your children, so you’ll take withdrawals equal to the investment return. Here’s what it looks like in the first year, with figures rounded to the nearest dollar:

After that first-year withdrawal, the ACB is reduced to $94,340 to account for the $5,660 ROC, but you still have $100,000 invested. The second year’s withdrawal will net to $5,868, for an effective tax rate of 2.2%. It will take over 100 years for the effective tax rate to round to the actual 20.0% rate on taxable capital gains.

Though you will have maintained the principal amount invested, the continuing reduction in the ACB means that an increasing portion of your investment will be taxable. If you never sell, there will still be a deemed disposition at your death (though this could be deferred by rolling it at ACB to your spouse), before passing on to your children as desired.

Scenario 2 – Equal spendable withdrawals, depleting principal

Instead of allowing the net withdrawal to be reduced each year, you may prefer to have a consistent after-tax spendable amount. If you want $6,000 in your hands, you would need to withdraw/redeem more than that in order to account for taxes. That would only be another $69 in year 1, but the extra amount would increase each year.

While this slowly depletes the principal, even at year 25 you will still have about $70,000 invested.

Scenario 3 – Indexed withdrawals, eventually exhausting principal

As the years roll on, the flat amount of withdrawals under either of the preceding scenarios will lose purchasing power due to inflation. Rather than passing on the principal to your children, your priority may be to use this money to take care of your own living expenses. To do so, you could index the withdrawals each year.

The current inflation rate recommended in the 2024 FP Canada Projection Assumption Guidelines is 2.1%. At that rate, you could sustain an indexed $6,000 spendable withdrawal from $100,000 of principal for about 25 years.