Prudence, perks & pitfalls in property transfer

Joint ownership is often the way that spouse/common-law partners (CLP) will own their matrimonial home, a recreational property and maybe other real estate held for investment. But when other owners are contemplated to be involved – for example, adult children – another arrangement may be more appropriate, including just leaving well enough alone.

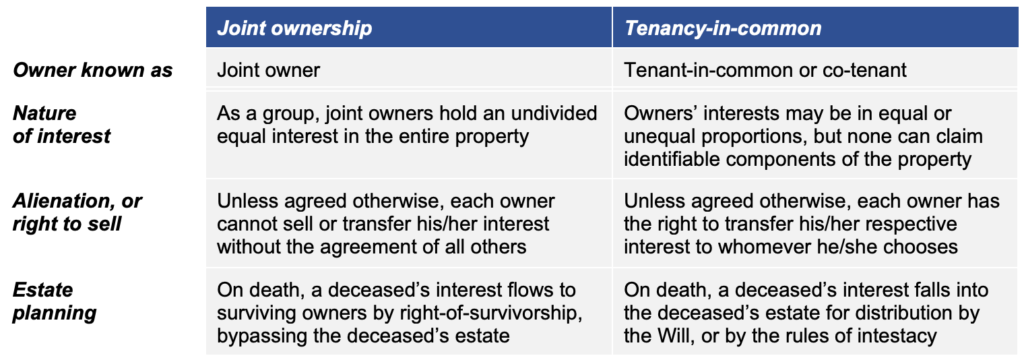

Compared to tenancy-in-common

There are two common ways that property is owned by more than one person, joint ownership and tenancy-in-common, with a few key features distinguishing them:

Probate avoidance

Probate is the tax or fee charged by a court for confirming that a submitted Will is valid for the named executor to deal with a deceased person’s estate. The formal name varies by province. Some provinces just charge a flat filing fee of a few hundred dollars, and in others it can be up to about 1.5% of the value of the estate property.

The choice between the types of property ownership is often influenced by a desire to avoid probate. Specifically, the right of survivorship under joint ownership allows for the interest/rights of a deceased owner to bypass his/her formal estate, thereby avoiding probate.

While probate could total up to a significant dollar figure when viewed in isolation, it is usually a relatively small proportion of the cost of administering an estate, and there are trade-offs to consider before deciding to proceed.

Couples’ preference for joint ownership

Spouse/CLPs usually intend the other to be the primary or only beneficiary of their estate. Joint ownership can therefore simplify the estate by passing selected property outside the Will. This can put things beyond the reach of a Will challenge, insulate against estate creditors, and again escape any probate fee/tax.

In addition, appreciated property can pass between spouse/CLPs at its cost base, allowing couples to add one another to title without triggering a tax bill on the capital gain.

Involving adult children – Tread carefully

As children are usually the next stage of beneficiaries after a spouse, it may at first seem a good idea to add one or more as joint owners with the parents, or after one parent dies. While this may indeed streamline the legal transfer, it is an action that should be balanced with other legal, financial and practical considerations.

Income tax effect of transfer to joint ownership

Unless it is clear that the parent retains the beneficial rights to the property, tax will generally be triggered when a non-spouse is added. For example, if two parents add their adult child as a joint owner on an investment property, they are deemed to dispose of 1/3 of the property, thereby triggering tax on 1/3 of the current capital gain. A tax professional can advise the parents on appropriate steps and recordkeeping if they wish to avoid this result.

Relief and risk if it is a principal residence

A variation of the example above would be to put a child on title of the parents’ principal residence. While their principal residence exemption (PRE) may protect against capital gains tax when the child is added, if the property is not also the child’s own principal residence, future capital gains on the child’s portion may very well be taxable.

Legal and registration cost

Costs of transfer should be balanced with expected probate tax savings. According to province (and even regions within), taxes or fees on land transfers may be flat charges or be based on a percentage of the property value. Transfers to a spouse/CLP are often exempt, extending in some provinces to certain intra-family transfers.

Exposure to creditors of other joint owner(s)

If an added child runs into debt problems, creditors may decide to take legal action against the property. While the creditors’ claim will be limited to that child’s interest, if neither parents nor child have other assets to satisfy the claim, the creditors could force sale of the property to collect the amount due.

Matrimonial law implications

Adding a child as a joint owner may expose their interest to a property equalization claim on a later relationship breakdown. In most provinces if it is a gift to the child, then in principle it is not exposed, but this could be affected by how the property is used thereafter. In Ontario for example, a recreational property that is regularly used by a married couple may be considered a matrimonial home, making the value of the ownership interest equalizable.

Legal or beneficial transfer, and estate complications

When an adult child is gratuitously added as a joint owner, that is presumed not to be a beneficial transfer. On the parent’s death, the child holds the property as trustee for the estate beneficiaries. The presumption can be rebutted if the parent expressed otherwise at the time of the transfer, ideally in writing. This would be particularly important if there are other siblings not on title, especially if there is any existing family tension. Otherwise, the onus is on the child to prove to a judge that the parent intended that that child personally succeed to the property.

Application to financial accounts and other personal property

Property means something that can be owned, whether that’s real property (or real estate) or personal property. Personal property covers moveable things, including financial instruments like chequing and savings accounts, and non-registered accounts holding GIC/term deposits, individual marketable securities or mutual funds.

Joint ownership can also be used with personal property. As with real property, this can simplify and streamline estate transfers between spouse/CLPs, and where others are involved the cautions above again apply.