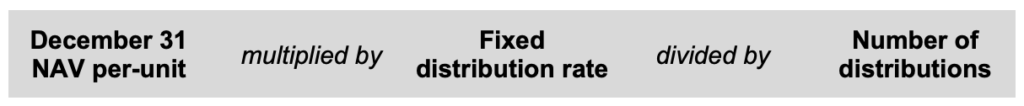

The whole story on half of the returns

Mutual funds provide a streamlined way to make a single purchase of a portfolio of securities. By pooling with others, an investor has a cost-effective way to participate in a chosen investment mandate that would be challenging to assemble and maintain individually.

When holding individual securities, an investor’s total return is a combination of the income earned by that security for a given period and the change in its price over that same period.

The same holds true when securities are pooled in a mutual fund. The netting of the ups and downs of individual prices is reflected in the change in the fund’s net asset value (NAV), while the sum of all the securities’ incomes becomes the fund’s periodic distribution to investors.

Why distribute a mutual fund’s income?

In Canada, an investment manager may create a mutual fund in one of two legal structures: trust or corporation. By both number of funds and assets under management, the trust form is significantly more common. Except where noted otherwise, this article deals with mutual fund trusts.

Once a mutual fund is created, the manager will make it available for investor deposits, charging the fund for its administration and investment management services. Such charges are calculated and expressed as a percentage of the fund’s investment assets, known as the management expense ratio (MER).

A mutual fund is taxable on the income from its investment holdings, though it is allowed to deduct the expenses it incurs in earning that income, which is mainly that MER. Regardless which of the two legal forms it takes, a mutual fund is subject to very high tax rates, roughly the same as what a top tax bracket individual would pay.

If a mutual fund had to pay tax itself, that would be costly for the overwhelming majority of its investors—who are not at top bracket—and exceedingly so when held in a registered plan that does not pay tax while earning income. This includes a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP), Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF), Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP), Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP), or Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA).

Limiting tax on investment income

Rather than impose its high tax rate on investors, a mutual fund will absorb sufficient income to deduct the full MER charged by the investment manager. It will then distribute the remaining income to investors according to their proportion of ownership, to be taxed to each at their respective income brackets—or in the case of RRSPs and other registered accounts, with zero tax applying on those distributions.

Facilitating more invested capital

Distributions can also indirectly increase the capital a mutual fund has available to invest. As discussed further on, investors can receive distributions in the form of cash, or allow that amount to be reinvested on their behalf in more units of the fund.

For investors with current spending needs, for example those in their retirement years, a cash distribution will allow them to pay the associated tax and spend the net income on their living expenses.

If the automated reinvestment route is chosen—which is the default choice for most mutual funds, with investors entitled to opt out—the fund will have both the original capital and that year’s income for continuing investment. Or, if an investor takes the cash distribution, part of that could be used to pay the tax, with the difference available for the investor to reinvest in the fund. In the former case the gross amount is reinvested, and in the latter, it is the net amount. Either way the use of the investors’ lower tax rates assures the lowest tax and highest reinvestment.

Form of income distribution

In addition to being taxable to investors rather than the fund, distributions retain their tax character when received by investors. Still, one must distinguish whether the mutual fund is in a registered or non-registered account.

Registered accounts

Income type is irrelevant in registered accounts, as no tax is charged on income or growth while in such plans. On money coming out of the plan, taxable withdrawals are treated as regular income up through the recipient’s graduated tax brackets, regardless of the original income type when received. The notable exception is a TFSA, for which there is no tax on either internal income or growth, or withdrawals.

Non-registered accounts

For non-registered accounts, the investor is taxed in the year of receipt, according to income type:

Interest – Fully taxable, according to the investor’s graduated bracket rate.

Foreign dividends – Fully taxable, according to the investor’s graduated bracket rate. Usually, the issuing corporation is obligated to withhold tax in the foreign jurisdiction before paying the net amount to the mutual fund. When this is distributed to the investor, the mutual fund typically is able to report the details of what was withheld, allowing the investor to claim a foreign tax credit when calculating (reducing) their Canadian tax obligation.

Canadian dividends – A two-stage gross-up and tax credit process applies to Canadian dividends received by a Canadian resident investor, whether received directly or via mutual fund distribution. Mutual fund distributions are most often eligible dividends, being those originating from publicly traded Canadian corporations, though on occasion there may be non-eligible dividends sourced from a Canadian-controlled private corporation. Either way, the two-step procedure results in a preferred tax rate for the investor, which is roughly the difference between the investor’s marginal tax rate and the amount of Canadian tax the originating corporation has already paid.

Net capital gains – The mutual fund tallies all its capital gains and losses on trading transactions over the course of its taxation year, and reports the net capital gain to investors. Under current rules, half of the capital gain is taxable. If the mutual fund is in a net capital loss position, that loss cannot be distributed to investors, but can be carried forward to reduce the fund’s future capital gains.

Return of capital (ROC) – Rather than being income, this is a return of the investor’s own capital. There is no tax on such capital, but, as discussed in greater detail elsewhere in this article, it reduces the investor’s adjusted cost base (ACB) in the mutual fund. When the investor has a future disposition of part or all of the mutual fund, this reduced ACB contributes to an increase in the capital gain—or a decrease in the capital loss—on that transaction.

Effect on mutual fund’s NAV

A mutual fund’s assets are a total of the securities it owns and the cash it holds when income is paid from those securities. When that cash is distributed to investors, there is a corresponding reduction in the fund’s assets.

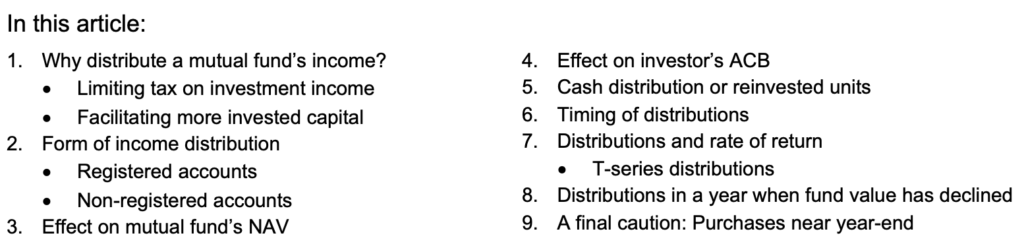

To illustrate, assume a mutual fund trust with 1,000 outstanding units is holding securities with a combined fair market value (FMV) of $10,000, and $600 of distributable income after deduction of the MER. To isolate the effect of the distribution on NAV, the example assumes no change in market value.

On the left, Table 1A shows the mutual fund before and after the distribution, and viewed in isolation may give the impression that $600 has been lost on the total assets line. But in Table 1B on the right, consider the investor who initially had 100 units worth $1,060, who now has $1,000 value in the mutual fund plus $60 of distributed cash.

Project those 100 units up to the 1,000 units held by all investors to arrive at the $10,000 of remaining mutual fund value, to which can be added the $600 in investors’ hands collectively. Total assets remain intact at $10,600.

Effect on investor’s ACB

Most often, an investor’s adjusted cost base (ACB) is simply acquisition cost. That said, there may be some adjustments. For example, it may be increased by purchase costs such as commissions.

Fund distributions interact with the investor’s ACB as follows:

-

- A cash distribution of income from a mutual fund has no effect on an investor’s ACB.

- Distribution by reinvestment in units of the fund increases the investor’s ACB. The investor must still pay tax on that reinvested amount, but as the fund did not distribute any cash to the investor, another source must be used to pay the associated tax.

- ROC distributions reduce an investor’s ACB, though that reduction will be restored to the extent that an investor reinvests some or all of the distribution. If the fund’s ACB is zero or negative, ROC distributions are treated as capital gains.

In the case of registered accounts, the concept of ACB does not apply. However, such accounts are subject to maximum contribution limits and may have minimum withdrawal requirements. A distribution from a mutual fund into a registered account has no effect on the calculation of either contributions or withdrawals.

Cash distribution or reinvested units

An investor may receive a distribution in cash or may instead accept the mutual fund’s offer to reinvest the otherwise distributable income. Whether taken in cash as shown in Tables 1A & 1B above or as a reinvestment in units of the fund, the tax result for the investor is the same.

To show this as a continuation of the foregoing example, we’ll assume the $60 distribution is interest and that the investor is at a 50% marginal tax rate, resulting in $30 tax due. We’ll further assume that $800 was originally invested, using that as the ACB to arrive at the investor’s final financial position after disposing of the mutual fund.

The second stage disposition illustrates how the investor is in the same tax position by either of the two routes. To be clear though, that is true whether or not the disposition happens at that time. In reality, the investor will likely continue to own the fund over many years, with more contributions, income distributions and withdrawals along the way—while the effect of the reinvestment remains baked-in, just as if it had been a cash distribution.

The second stage disposition illustrates how the investor is in the same tax position by either of the two routes. To be clear though, that is true whether or not the disposition happens at that time. In reality, the investor will likely continue to own the fund over many years, with more contributions, income distributions and withdrawals along the way—while the effect of the reinvestment remains baked-in, just as if it had been a cash distribution.

Timing of distributions

Distributions may vary based on a fund’s performance or may be at a fixed rate. Common scheduled intervals are monthly, quarterly, semi-annual or annual, with interest and dividend income usually distributed during the year, and net capital gains distributed at year-end. Distributions are paid to unitholders as of a set record date, generally the business day prior to the respective distribution date.

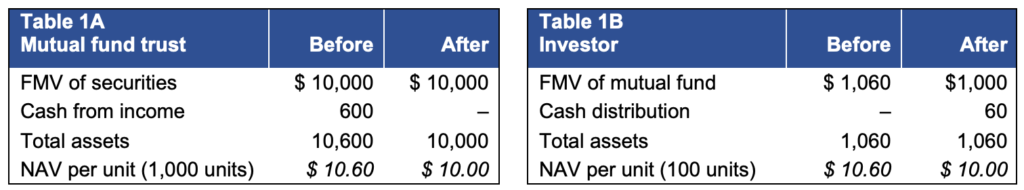

Funds with a fixed rate distribution calculate their coming year’s projected distributions based on the NAV per unit as of the preceding calendar year-end, using the formula:

For example, a fund on a monthly distribution schedule with a $12.00 NAV at December 31 of the preceding year and a 4% fixed distribution rate would have a per-unit distribution of $0.04 [$12.00 x 4% ÷ 12]. An investor with 10,000 units would expect to receive $400 each month.

For example, a fund on a monthly distribution schedule with a $12.00 NAV at December 31 of the preceding year and a 4% fixed distribution rate would have a per-unit distribution of $0.04 [$12.00 x 4% ÷ 12]. An investor with 10,000 units would expect to receive $400 each month.

Distributions and rate of return

While distributions are designed to allocate a fund’s income to investors, this should not be confused with rate of return. A fixed distribution rate is a commitment to periodically distribute a certain dollar value out of a fund’s assets—and may be premised on expected returns—but is not a guarantee of a fund’s rate of return.

Similarly, there may be an expectation of the income types making up that distribution based on the fund’s investment parameters, but the actual composition of distributions cannot be known until the fund does its

year-end accounting. Only then can distributions be reconciled with the type and amount of income earned.

If distributions exceed income, the excess is a return of the investor’s own capital (ROC). The income is part of the investment return calculation, while ROC is not. Details will be reported on the investor’s T3 tax slip.

T-series distributions

Some mutual funds allow investors to choose a distribution rate that is intentionally higher than the income the fund expects to realize in the year. “T-series” is the common term investment managers use to describe these arrangements, with the “T” highlighting the tax effect of this type of distribution.

The result is that most or all of the distributions will be non-taxable ROC, which can be appealing to someone presently at a high tax bracket who anticipates being at a lower bracket in future. Another candidate may be an Old Age Security pensioner, or other recipient of income-tested benefits, who wishes to stay below an income threshold beyond which such benefits would be reduced or clawed back.

Though this approach may be effective in addressing near-term goals, investors should bear in mind that a high T-series rate (historically, 8% or more has been available) will deplete the value of holdings over time if it consistently exceeds the fund’s rate of return.

As well, successive ROC distributions grind down the investor’s ACB, increasing the eventual capital gain on future withdrawals. This can be especially costly on a deemed disposition at death if there is no spouse to whom the investment can be rolled over to, as the entire gain will be taxable in a single year, likely at higher tax bracket rates than if it had been drawn down over multiple years.

Distributions in a year when fund value has declined

Investors may be surprised to receive reported income on their annual T3 slip from a mutual fund in a year when the fund’s value has fallen. As noted earlier, distributions and rate of return are different concepts. To explain what’s going on here, one can look back to the two components of a mutual fund’s total return: price change and income earned.

Over multiple years, investors generally expect to see a combination of a net increase in the price of securities owned, and income being generated from those securities. However, in any one year, it is possible for income to be earned and paid out to investors, while the fund’s price declines. Depending on the investment mandate, and how actively securities have been traded in a year, it may even be possible to have net capital gain distributions even if the value of the fund is down from the previous year-end.

While receiving a distribution in a down year is not a happy occasion, the positive to be taken out of it is that the income components of the fund have continued to play their role, despite the downward price pressure. In addition to softening the fall by contributing income to counter the price drop, that income is being deployed opportunistically. Assuming the fund’s mandate still fits the investor’s longer-term goals, reinvested distributions will be acquiring fund units at a bargain cost, positioning the investor to participate in the price rebound.

A final caution: Purchases near year-end

Over the course of a year, an investment manager buys and sells securities as appropriate to fulfill the fund’s investment mandate. As noted earlier, the capital gains and losses on those trades are tallied so that the net capital gain can be reported to investors. Just as interim income distributions are reported to unitholders as of a record date, the same applies to the year-end distribution. Depending on the fund, that date is generally mid to late December – and this is where the danger arises with non-registered mutual fund purchases late in the year.

An investor who purchases a mutual fund shortly before the record date is buying an appreciated asset, to their detriment. Adapting the example in Table 1A & 1B above to be shortly before the year-end record date:

-

- The $10,600 ‘before’ value can be viewed as including a $600 net capital gain waiting to be distributed.

- Just before the record date, an investor buys 100 units for $1,060, being both the ACB and FMV.

- The fund distributes by a reinvestment of units, causing the investor to pay tax on a $60 capital gain.

- The reinvestment increases the investor’s ACB by $60 to $1,120, while the FMV remains $1,060.

Having only bought into the fund for a day or two, the investor is paying tax on a full year’s worth of activity. This could have been avoided by waiting just a few days. Some solace can be taken that there is now a built-in $60 capital loss on the investment that will reduce future capital gains…eventually!

Importantly, as distributions into registered accounts are not taxable, this is not a problem there.