7×7 questions to frame your future

Your business is the source of your income, and the store of years of hard work. But despite your dedication as an entrepreneur, there will likely come a time when your focus shifts toward harvesting that value and moving on to the next stage of your life.

Whether you’re thinking of selling or succession, it can be a complicated and time-consuming process. Setting the stage for the technical guidance from your legal and tax advisors, here are some questions to help prepare you and your business for succession, grouped as follows:

1. You personally – Financial planning perspective

2. Understanding you in the business

3. Your family and your business

4. Your people – Key players in the enterprise

5. Your time – Planning, closing and post deal date

6. Your payday – Who’s paying, how much & when

7. Your estate planning

1. You personally – Financial planning perspective

Financial planning is about where you are financially, where you’re headed, and how you’ll get there. It’s extra complicated for business owners, because the source of your income is also the store of a significant portion of your wealth – the old goose and golden egg situation. Still, we need to start and end with what it means on the personal level.

-

- Do you have a written personal financial plan?

- Are parts of your personal finances tied to the business, and do you know how you’ll make that break?

- Are you comfortable with your spending habits now, and what that will look like in your later years?

- Have you put your personal debt behind you, or do have a plan to get there?

- How much do you expect to realize from the business –or– how much must you realize to meet your needs?

- Do you understand investment markets, retirement savings plans and public pensions?

- How will you spend your time in your post-business years, whether or not you call it ‘retirement’?

2. Understanding you in the business

You need clarity on your importance to the business, to know what business you have to transfer. This is a cold hard look at your value in the business, so that it’s clear what is left when you are out of it. Think of this in terms of both personal satisfaction and financial return, then ask these questions about yourself and about your potential suitors/successors.

-

- Do you have a special entrepreneurial passion that makes the whole worth more than the sum of its parts?

- What technical skills, regulatory licences and proprietary knowledge are required to run this business?

- How much does your management experience and leadership factor into the business’ success?

- In all cases above, how long will it take to cultivate or transfer those elements to someone else?

- All that in mind, is this or can it be a self-sustaining business that can operate independent of who owns it?

- Alternatively, is this an occupation that requires a skilled substitute in place of you?

- Or finally, is the business uniquely you, and if so, what implication does that have for winding-down?

3. Your family and your business

Here’s your second cold hard look, this time at the people you care most about – your family. As tough as it may sound, your first priority must be to make sure that you realize from the business what you need to meet your own financial needs. That said, one of those goals is usually caring for family, individually and collectively, which in turn presents its own challenges.

-

- Who among your children/family have the skills to carry on the business?

- What skills may be lacking, how can they be obtained, and how long will that take?

- Who among the family expect to be future owners, and are you managing those expectations?

- What interpersonal conflicts have you observed, and will those get better or worse in your absence?

- Will those left out of leadership be content to continue in supporting roles as employees?

- Is it viable to have non-active owners, and how do you shield the active ones from any interference?

- Whether the transfer is a buyout or inheritance, how will you provide for those excluded – or will you?

4. Your people – Key players in the enterprise

As much as a business is an economic endeavour, it requires people to make it work. And in a small business, there is often a close connection with and among those people. These may be the future buyers of the business, or at least continuing contributors, so it’s important to know where opportunities and exposure may lie.

-

- Who are your key people in the business?

- When was the last time that you updated their job descriptions?

- Do they have critical knowledge or skills, the loss of which would endanger the business?

- Do you have employment contracts that include non-competition & non-solicitation terms?

- Are there operations manuals for all your main business processes?

- What are their expectations of continuing employment and/or eventual ownership?

- Upon an ownership change, would they remain with the business?

5. Your time – Planning, closing and post deal date

Running a business is one thing; arranging for its transfer is another. With family or internal buyers, it can be years of grooming. With an outsider, a get-to-know-you time period will be followed by a more formal due diligence process where you can take the lead from your legal and accounting advisors. Either way, it takes time.

-

- For arm’s length transfers to colleagues or family, is there a documented plan with agreed timelines?

- For non-arm’s length, practically how much time will it take to identify and close with a successor?

- In due diligence, how much time can you be away from the business without it being a strain?

- How long will your successor want you to remain to support the transition, and will you be compensated?

- With current business partners, do you have an executed buy-sell agreement?

- On disability or death, is each financially capable of carrying out the buy-sell, and/or is there insurance?

- If your successor is paying over the course of years,is there insurance in case of that person’s death?

6. Your payday – Who’s paying, how much and when?

The old adage is that a business is worth what someone is willing to pay. In a family succession, perhaps it’s what the owner may be willing to accept. As you look to determine value, whether in a sales negotiation or setting up for succession, you will need to come to a value first, and then determine how the transaction will be structured.

-

- What sustainable free cash flow does the business generate? (Discuss with a business valuator.)

- What’s the difference in value to you operating the business, versus someone paying to buy it from you?

- Assuming a corporation, will the sale/transfer be the assets or shares?

- Will payment happen all at once on the closing date, or in instalments over some years?

- Will future payments be charged interest and/or be adjusted by future performance of the business?

- For payments over time, can capital gains recognition be deferred to later years, and how long?

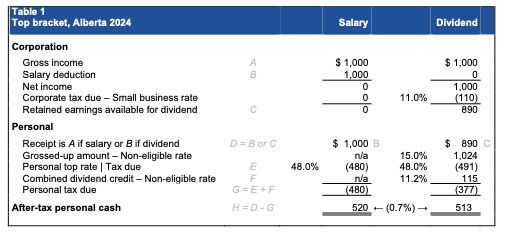

- How will payments be taxed, and for a corporation, do shares qualify for the lifetime capital gains exemption?

7. Your estate planning

The best laid plans can be unravelled if there is no adequate safety net to deal with untimely events like disability and death. These are personal tragedies that can be compounded when a business is involved. Whether you are in the process of running the business or turning your attention to passing it on, estate planning is good business planning.

-

- Do you have a Will that has been drafted with the business in mind?

- To support your executor, have you identified a steward who knows and can manage the business?

- Do you have Powers of Attorney for property & personal care, or a POA specific to the business?

- Is it worth having a secondary Will that isolates business corporation shares from probate exposure?

- For a complex business, have you considered a trust as part of the business ownership structure?

- Do your corporate documents allow for operation of an attorney or executor, as the case may be?

- For any tax-deferred transfers, have you arranged life insurance to settle any remaining tax liability?