Buying, owning, renting and selling

Whether as sunny or snowy vacationers, dedicated urbanites or rural explorers, we Canadians spend a lot of time in the US – and that can also mean spending a lot of dollars. For those who are repeat renting visitors, the idea is bound to come up: Why not buy?

Real estate ownership is a big financial step, especially so if you’re thinking about distant property, with extra complexity when looking across the border into the United States.

This article identifies key tax and estate issues that Canadian would-be purchasers and existing titleholders should know when owning US real estate.

Being a non-resident buyer of US real estate

As a Canadian, you don’t require a special permit to own US real estate. Still, there are differences in how the real estate industry operates in the US, in particular how your legal rights are protected. In Canada, lawyers generally oversee the closing and title registration process, which may include obtaining title insurance. Comparatively, title insurance companies take the lead in many states, in place of some or all of what lawyers do here. It’s important for you to understand who represents you and how, before being marshalled through an unfamiliar system.

In a similar vein, you can obtain a mortgage from an American lender without having to jump over regulatory hurdles aimed at foreigners, but of course subject to the lender’s business criteria. Even so, you’ll need to allow more time for due diligence and preparation as compared to your familiar domestic Canadian deal. That’s because US lenders generally require more documentary disclosure, with added scrutiny when foreigners are involved. It will take time for you to understand, identify, collect and transmit documents (including Canadian credit score, income tax returns and relevant financial statements), and then for the lender to in turn verify, evaluate and approve before proceeding.

Who might hold title, and how?

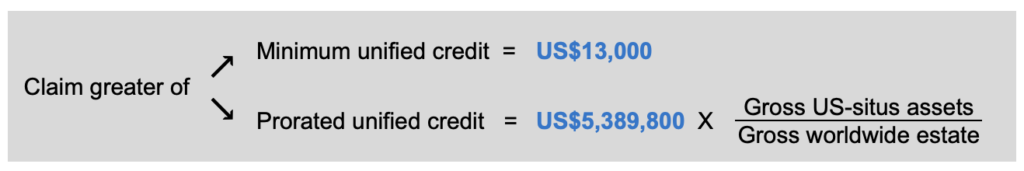

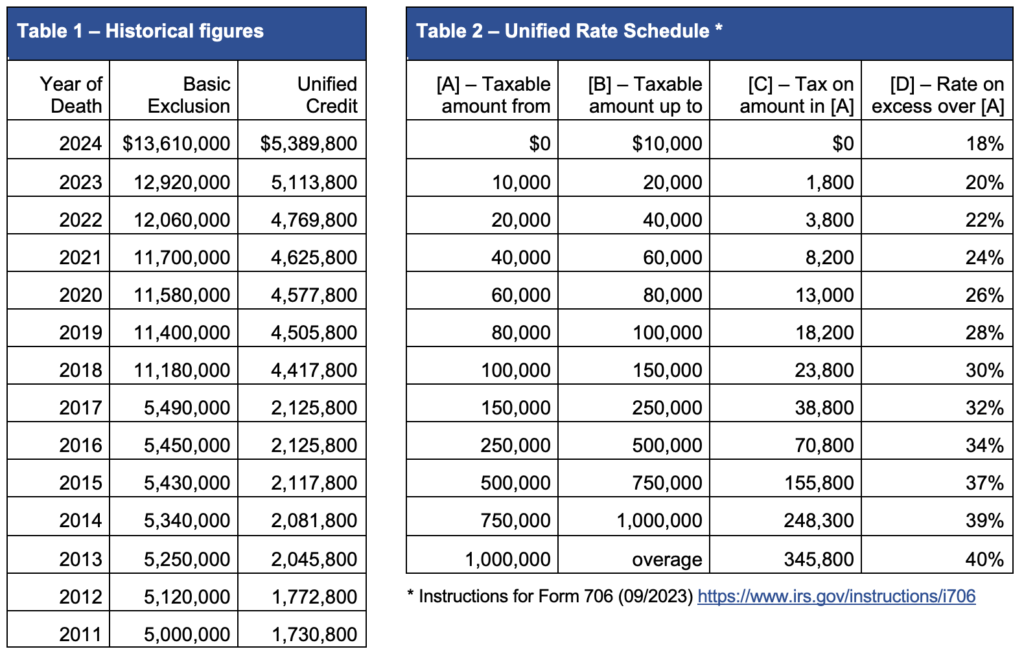

As in Canada, US real estate may be owned individually, with others, or through another legal structure. Many of the same issues influence choices on either side of the border, with the added concern in the US about exposure to its Estate Tax. Though important to be aware of, a deceased foreigner’s worldwide assets would have to be worth over US$13 million in 2024 for any amount of such tax to be owing. For a deeper discussion of the US Estate Tax, see our article US Estate Tax & Estate Returns – For Canadians.

That aside, sole owners will probably register title directly in their own name, while spouses typically default to joint tenancy with right of survivorship (JTWROS), and multiple owners who are not spouses tend to prefer tenancy-in-common (TIC) whereby each maintains testamentary control of their proportionate interest. Though these are the common expectations, spouses could register TIC or in one name only, and non-spouses could choose JTWROS.

It is prudent to obtain independent legal advice as to the tax effects and succession rights under all options.

In terms of other legal structures, it is possible to use a corporation, trust or partnership, in all cases usually preferred to be resident in Canada, but possibly US resident. This extra layer adds legal complexity and maintenance costs, and possibly higher Canadian tax exposure. In most cases, the direct ownership options above will suffice, but a qualified professional can advise if there are exceptional reasons to proceed otherwise.

Revisiting ownership through a Canadian corporation or trust

Historically many Canadians used a sole-purpose corporation to hold US vacation property. However, in 2004 the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) began imposing a taxable shareholder benefit for personal use of corporate property, which then swung the preference toward trusts over corporations when layered ownership was desired.

More recently as of June 25, 2024, both trusts and corporations face 2/3 income inclusion on all capital gains, while individuals can still use the 1/2 rate on up to $250,000 of capital gains in a year. This may influence toward holding title in personal name(s), given that large capital gains can arise on the eventual sale of real estate. Qualified cross-border legal and tax advice should be obtained before initiating or changing ownership registration.

US legal implications (or not) of ownership

In some countries, foreigners gain residential rights by purchasing land, for example the right to remain there longer than mere visitors. While there are occasional large-scale business incentive programs, there is no such rule in the US for personal-use real estate. And don’t be misled by rumours of favoured status being extended to ‘snowbird’ Canadians, as is recurringly speculated in popular and social media, but has never come close to legal reality.

For some comfort from the US tax perspective, one is not automatically required to file a US tax return just because US real estate is owned. However, annual US tax filing will usually be necessary when a property is rented, as well as when there is a disposition. Sometimes that is under your control, like when you choose to sell, but tax can also apply on a deemed disposition such as a gift of a property interest or upon an owner’s death.

Accounting for rental income

Again, one may be required to file an annual US tax return if rental income is earned, but not necessarily. First, there is an exception from filing if a US vacation property is rented for less than 15 days in a year. Beyond that, the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) allows foreign owners to choose between two treatment options.

Option 1 – Gross rental income, without filing a US tax return

This is the simpler (though possibly more costly) option, whereby a 30% tax is paid on gross rental income, without having to file a US tax return. The tax is withheld by the tenant or by the foreign owner’s local property manager, and remitted directly to the IRS. Two forms must be filed annually, the first showing the arithmetic of the withholding tax calculation, and the second with further financial and personal information about the foreign owner(s):

-

- Form 1042, Annual Withholding Tax Return for U.S. Source Income of Foreign Persons

- Form 1042-S, Foreign Person’s U.S. Source Income Subject to Withholding

As a Canadian resident subject to tax on worldwide income, the rental income would also be reported on your Canadian tax return. Deductions may be taken to arrive at the net rental income, against which a foreign tax credit (FTC) may be claimed, up to the lesser of US tax paid and the Canadian tax due on that US source income. Given the 30% US withholding rate on the gross rent, it is possible that some US tax would not be fully recovered.

Option 2 – Net rental income, requiring filing of a US tax return

Alternatively, one may report on a net rental income basis, effectively treating the activity as a business. This allows for the use of US graduated tax rates (rather than the flat 30% withholding rate) applied on net income after deductions. Many deductions will be the same in both countries, like utilities, property tax and management fees. But the systems also diverge in key respects, such as mandatory depreciation claim in the US (elective in Canada), broader mortgage interest deductibility in the US, and differing approaches to rental losses. These differences can lead to mismatched type and timing of deductions, so be sure that your Canadian and US professionals are coordinated.

Despite the accounting challenges, the net option will likely reduce the US tax liability, while concurrently increasing the likelihood of fully utilizing the FTC on your Canadian tax return. To file a US non-resident tax return, one must first have an individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN), similar to a social insurance number (SIN) for Canadian domestic tax filing. In sequence, the forms are:

-

- Form W-7, Application for IRS Individual Taxpayer Identification Number – The IRS processing time to issue an ITIN is about 7 weeks, or 11 weeks at peak times (January-April) or when applying from abroad.

- 1040-NR, U.S. Nonresident Alien Income Tax Return – For annual income tax reporting. If only reporting rental income (technically part of “income effectively connected with US trade or business”), the due date is June 15th following the taxation year, or the next business day if that is on a weekend. If other income is being reported, the filing due date may instead be April 15th. Confirm with a US tax professional.

The tenant would need to be given an official release so that the otherwise 30% is not withheld from rent. This is achieved by providing the tenant a Form W-8ECI Certificate of Foreign Person’s Claim That Income Is Effectively Connected With the Conduct of a Trade or Business in the United States. This form is not sent to the IRS, but

Form 1042 and Form 1042-S must still be filed, either by you or your property manager if you employ one.

Importantly, once the election is made to use net reporting, it applies to all US real estate owned, and to the current and all future tax years. The only way to revoke that is with consent from the IRS, which is infrequently granted. With this in mind, some people may be content to use the gross method as a new owner (if the expected cost difference is not too steep), thereby preserving the flexibility to change to the net method in future if it better suits their evolved needs.

Selling US real estate

When it comes time to move on from owning that US property, there are three main tax issues to address:

-

- US withholding tax

- US income tax reporting as a non-resident

- Canadian income tax reporting

US withholding tax

A purchaser/transferee of US real estate from a foreign owner is obliged to withhold 15% of the proceeds and remit it to the IRS. There are two forms for this purpose:

-

- Form 8288, U.S. Withholding Tax Return for Dispositions by Foreign Persons of U.S. Real Property Interests

- Form 8288-A, Statement of Withholding on Dispositions by Foreign Persons of U.S. Real Property Interests

Form 8288 accompanies and provides the arithmetic of the withheld tax, being due by the 20th day after closing, with interest and penalties imposed on the purchaser if it is late. A Form 8288-A must be included for each transferor/seller, a stamped copy of which will be sent by the IRS to each transferor to be attached to their US tax return to receive credit for any tax withheld. Following here are the three most common exceptions to the withholding requirement when a non-resident individual disposes of US real estate.

Exception 1 – Sales price below US$300,000, and future use as a residence

No withholding is required if the purchaser acquires the property as a residence and the sales price is below US$300,000. The buyer or a family member must have definite plans to reside at the property for at least 50% of the days the property is used by any person during each of the first two 12-month periods following the closing date.

Exception 2 – Sales price from US$300,000 to $US 1 million, and future use as a residence

If the purchaser acquires the property as a residence as outlined above, and the sales price is no more than

US$1 million, withholding is still required, but at a reduced 10% rate.

Exception 3 – Withheld amount exceeds the transferor’s tax liability

If you as seller expect your US income tax liability on the capital gain to be less than the withholding rate, you can apply to the IRS for reduced withholding. To release the purchaser from the withholding obligation, a withholding certificate must be in-hand prior to closing. The seller/transferor applies for this using Form 8288-B, Application for Withholding Certificate for Dispositions by Foreign Persons of U.S. Real Property Interests. According to the form instructions, the IRS will normally act on an application by the 90th day after a complete application is received.

US income tax reporting as a non-resident

As on the advice side before taking action, it is highly recommended to hire qualified US tax advisors when it comes to fulfilling reporting/compliance tasks. The sale of US real estate by a non-resident owner is complex and beyond the scope of this article, so just briefly here are some ways the proceeds of sale may be treated for US reporting:

Adjusted cost basis (ACB) – This is what the owner originally paid for the property, less costs of acquisition & disposition and periodic depreciation claims, plus costs for capital improvements – Non-taxable

Long-term capital gains – The difference between sale proceeds and ACB is a capital gain (subject to recapture of deductions as discussed further on) – Currently taxed at 0%, 15% or 20%, depending on income level

Short-term capital gains – When capital property is held for less than 12 months, the capital gain component of the sale proceeds is taxed as regular income – Graduated tax rates between 10% and 37%

Recaptured depreciation – Cumulative deducted/claimed depreciation (mandatory under net rental income option) is re-included in income, before any capital gain is determined – Graduated tax rates between 10% and 37%

Unrecaptured section 1250 gain – An adjustment to recapture when an accelerated depreciation method has been used, above what would apply using a straight-line method – Usually at a 25% maximum tax rate

Principal residence for US tax purposes

Up to US$250,000 of capital gains may be excluded from tax on sale of a principal residence. The property must have been used a primary residence for at least 2 of the 5 years prior to sale. As it must also be the owner’s ‘main’ home, it is possible but unlikely for this last requirement to apply for a Canadian who uses it as a vacation home.

Canadian income tax reporting

Recapture and capital gains on sale

To the extent that depreciation (technically capital cost allowance) has been claimed in annual tax reporting, the cost base of capital property is reduced. When sale proceeds are more than the undepreciated cost, there will be fully taxable recapture until exhausted, and capital gains above that. As noted earlier, as of June 25, 2024, trusts and corporations face 2/3 income inclusion on all capital gains, while individuals can use the 1/2 rate on up to $250,000 of capital gains in a year, with the 2/3 inclusion rate applying above that.

Principal residence exemption

The Canadian principal residence exemption (PRE) may be used to reduce or eliminate the capital gain on sale of a residence, whether in Canada or elsewhere. A property qualifies if it is ordinarily inhabited, but does not have to be one’s main home as required under US rules. If the PRE is claimed for Canadian reporting only, any US tax will not be available as a foreign tax credit, as there is no corresponding Canadian tax against which the FTC may be claimed. Alternatively, a sufficient number of years could be claimed to offset the FTC, leaving unused years available for future use of the PRE against other concurrently owned property.

Canadian T1135 foreign income verification

T1135 reporting may be required if one holds foreign property with a cost in excess of C$100,000. This would apply to outright investment property or even to a periodic vacation home that is rented most of the time. To be clear, this is an information reporting form to accompany one’s annual tax return, not an additional tax. Effectively it apprises the CRA that certain property exists, providing a paper trail to track eventual disposition and capital gain reporting.

Currency exchange rates

Apart from day-to-day cash needs when spending time at one’s property in the US, both the US and Canada require tax reporting and tax payments to be in their own currency. Canadians with US property will have to establish a banking relationship in the US, and/or be ready to engage in foreign exchange, wire transfers and cross-border online banking so that US currency is available for both small and large cash needs.

Beyond that, the movement of the exchange rate between the currencies can complicate tax reporting. For example, if the US property value drops while the US dollar rises against the Canadian dollar, a later sale could result in a capital gain in Canada and a capital loss in the US. It can get even more complicated depending on the nature of the property (eg., investment or personal use), distinctive or conflicting definitions, and differences in how tax credits and losses are handled.

Estate planning with cross-border assets

When real estate is owned in another jurisdiction, it is important to take appropriate steps to assure that the property is covered in one’s estate planning. This is true even when looking at provincial borders, and most certainly needed when international borders are involved. If one dies, a home province Will may ultimately have legal authority to deal with assets elsewhere, but it can be costly and time-consuming to re-seal/approve it through the courts and legal process of another jurisdiction.

A common recommendation is to execute a Will and Powers of Attorney (both property and personal care) under the guidance of a lawyer in a foreign jurisdiction where real estate is owned. By coordinating with the home jurisdiction lawyer, the foreign documents can be drafted so they are constrained to the subject property and jurisdiction, so as not to alter or revoke the core jurisdiction documents. At such time as it may be necessary for them to take effect, there will then be an existing relationship with a local professional who can advise and assist as required.