Public pensions for seniors based on residency in Canada

Old Age Security is the largest pension plan run by the Government of Canada, paid to over six million people. Eligibility is based on age and years of Canadian residency, and while not directly based on income, benefits are reduced over a certain income level.

No-one pays directly into OAS. Rather, pension recipients are paid out of current tax revenue, making it one of the government’s largest costs at over $50 billion annually.

In 2022, the government announced a permanent 10% increase to the OAS pension beginning in the month of a pensioner’s 75th birthday. This 10% increase does not affect the calculation of a pensioner’s Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS).

Who is eligible to receive OAS?

You must be at least age 65 to receive an OAS pension, and:

-

- If applying as a current Canadian resident, you must be either a Canadian citizen or legal resident, and have resided in Canada for at least 10 years since the age of 18.

- If applying from outside Canada, you must have been a Canadian citizen or legal resident the day before you left, and must have resided in Canada for at least 20 years since the age of 18.

Amount of the OAS pension – Taxable

The OAS pension is paid monthly, with amounts indexed each calendar quarter.

-

- For the third quarter of 2024, the full benefit is:

- $718 monthly, which annualizes to about $8,620, for those age 65 to 74, or

- $790 monthly, which annualizes to about $9,482, for those age 75 and over.

- For the third quarter of 2024, the full benefit is:

-

- The full pension is for those who have resided in Canada for at least 40 years after age 18. A reduction may apply if the person was not continuously in Canada for the 10 years preceding pension approval.

- A partial pension at the rate of 1/40th per year of residence after age 18 is available if the person resided in Canada for at least 10 years after age 18.

Application process and timeline

Canadian residents who have paid into the Canada Pension Plan receive a letter from Service Canada the month after turning age 64, advising that they are automatically enrolled for OAS the month after turning 65.

Otherwise, a person should apply to Service Canada, in paper or online, at least six months prior to the intended start month. Someone who has already reached age 65 may apply and receive up to 11 months of retroactive payments, with the first retroactive month as the start age for the continuing OAS pension.

Deferring OAS up to age 70, with a premium

A qualified individual may defer commencement of the OAS beyond age 65, up to age 70. The monthly pension is increased 0.6% for every month taken after age 65, rising as much as 36% if one waits to age 70.

-

- For the third quarter of 2024, that could increase the pension to as much as:

- $977 monthly ($11,636 annual equivalent) for those up to age 74, or

- $1,074 monthly ($12,893 annual equivalent) for those age 75 and over.

- For the third quarter of 2024, that could increase the pension to as much as:

Old Age Security pension recovery tax – The clawback

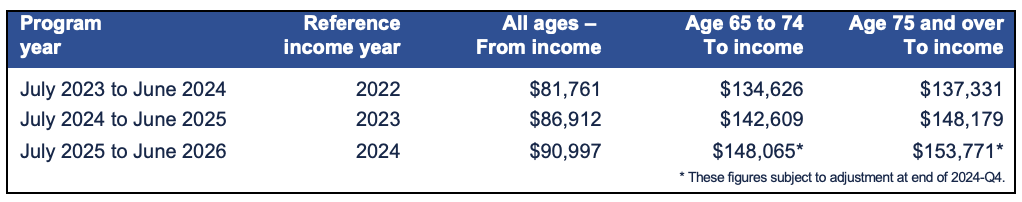

For each dollar of income over an indexed annual threshold, there is a 15% OAS recovery tax – or clawback. The clawback is based on net income in a reference calendar year, applied in the OAS program year following the tax reporting due date of that reference year, generally April 30th following the respective year-end.

Related benefits – Income-tested and non-taxable

Guaranteed income supplement (GIS)

The GIS is a monthly benefit added to the OAS pension of a low-income pensioner resident in Canada.

Spouse’s Allowance

If you are 60 to 64 years of age and your spouse or common-law partner is receiving the OAS pension and is eligible for the GIS, you may be eligible to receive this benefit.

Allowance for the Survivor

If you are 60 to 64 years of age and widowed, you may be eligible to receive this benefit.